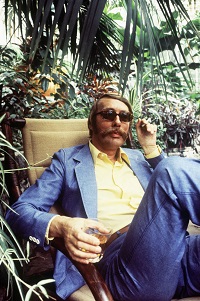

Dolce far niente

Summer Stars

Bend low again, night of summer stars.

So near you are, sky of summer stars,

So near, a long-arm man can pick off stars,

Pick off what he wants in the sky bowl,

So near you are, summer stars,

So near, strumming, strumming,

So lazy and hum-strumming.

Main St., Galesburg, de geboorteplaats van Carl Sandburg

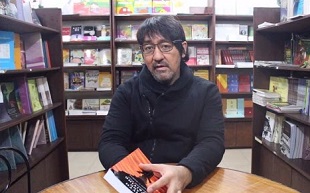

De Nederlandse schrijver Harry Mulisch werd geboren op 29 juli 1927 in Haarlem. Zie ook alle tags voor Harry Mulisch op dit blog.

Uit: De ontdekking van de hemel

“Waarop hij, Onno, hem vroeg of hij misschien niet goed bij zijn hoofd was om zo over zijn gasten te spreken, en of hij misschien wilde dat zijn schedel werd ingeslagen met een hollandse klomp. Iedereen sprakeloos. Hij kon fins praten! Na drie weken! Een oegrische taal! En toen hij het perplexe gezicht van zijn vader zag, dacht hij: — Ik ben je de baas, excellentie. `Ben je een zoon van die Quist?’ vroeg Max verrast. ‘Ja, die Quist.’ ‘Was hij voor de oorlog niet premier of zoiets?’ `Zou je misschien wat minder losjes over mijn vader willen spreken, Delius Max? De vier jaren van het kabinet-Quist behoren tot de donkerste van de menselijke beschaving. Het nederlandse volk zuchtte onder het theocratische schrikbewind van meneer mijn vader, — over wie ik geen kwaad woord wil horen, — en zeker niet uit de mond van iemand met zo’n ridicule automobiel.’ `Hij heeft ons in elk geval thuisgebracht,’ zei Max en stopte. ‘Zelf kun jij helemaal niet autorijden, als je het mij vraagt.’ `Natuurlijk niet! Waar zie je mij voor aan? Voor een chauffeur? Er zijn dingen die je niet mag kunnen. Wat je bij voorbeeld ook niet mag kunnen, is eten opscheppen met een vork en een lepel tussen de vingers van één hand, want dan ben je een ober. Dat kan jij natuurlijk ook, maar een heer als ik is niet gewend om zelf op te scheppen. Een heer als ik doet dat heel klungelig met twee handen en dan nog laat ik de helft op het tafellaken vallen, want zo hoort het.’ Bij het licht van de lantarens in de smalle straat konden zij elkaar nu beter zien. Onno vond, dat Max er eigenlijk veel te verzorgd uitzag om serieus genomen te kunnen worden; hij droeg het soort angelsaksische bourgeois outfit, met blazer en ruitjeshemd, dat hem ook bij zijn broers en zwagers zo tegenstond. Max, op zijn beurt, vond dat Onno geen slecht figuur zou slaan als orgeldraaier; ook zaten bij zijn oren en onder zijn kin verscheidene plekken, die hij bij het scheren had overgeslagen. Misschien was hij bijziend, kippig geworden van het turen naar ideogrammen. Onno stelde voor, naar Max’ huis te rijden; dan liep hij wel terug. Tevreden constateerden zij, dat er nog mensen op straat waren en dat overal in de huizen nog licht brandde, terwijl in Den Haag alle leven volledig was uitgewist. Bij het hoge hek langs het park sloot Max zijn auto af en trok zijn jas aan; Onno zag dat hij ook nog bruine peau de suède schoenen droeg. Hij wilde afscheid nemen, maar nu was het Max die zei: ‘Kom, ik loop een eind met je op.’ Uit de richting van het Leidseplein klonken politiesirenes: er was weer iets gaande, misschien de naweeën van een demonstratie tegen de Amerikanen in Vietnam.”

‘Ben jij ook eredoctor aan de universiteit van Uppsala?’ informeerde Onno. ‘Zoals ik?’ `Zo ver heb ik het nog niet gebracht.’ ‘Jij bent geen eredoctor aan de universiteit van Uppsala?’ riep Onno ontzet en bleef staan. ‘Kan iemand als ik dan eigenlijk wel met jou praten?’ Plotseling veranderde hij van toon, terwijl hij Max bleef aankijken. ‘Weet je dat jouw gezicht helemaal niet klopt? Je hebt staalharde, uiterst onsympathieke blauwe ogen, maar tegelijk een belachelijk weke mond, waarmee ik mij niet graag zou vertonen.’ Max keek naar hem op.”

Neil Newbon (Quinten Quist) en Jeroen Krabbé (Aartsengel Gabriël) in de verfilming uit 2001

De Koreaans-Amerikaanse schrijver Chang-Rae Lee werd geboren op 29 juli 1965 in Seoel. Zie ook alle tags voor Chang-Rae Lee op dit blog.

Uit: Native Speaker

„For a long time I was able to resist the idea of considering the list as a cheap parting shot, a last-ditch lob between our spoiling trenches. I took it instead as one long message, broken into parts, terse communiqués from her moments of despair. For this reason, I never considered the thing mean. In fact, I even appreciated its count, the clean cadence. And just as I was nearly ready to forget the whole idea of it, maybe even forgive it completely, like the Christ that my mother and father always wished I would know, I found a scrap of paper beneath our bed while I was cleaning. Her signature, again: False speaker of language.

Before she left I had started a new assignment, nothing itself terribly significant but I will say now it was the sort of thing that can clinch a person’s career. It’s the one you spend all your energy on, it bears the fullness of your thoughts until done, the kind of job that if you mess up you’ve got only one more chance to redeem.

I thought I was keeping my work secret from her, an effort that was getting easier all the time. Or so it seemed. We were hardly talking then, sitting down to our evening meal like boarders in a rooming house, reciting the usual, drawn-out exchanges of familiar news, bits of the day. When she asked after my latest assignment I answered that it was sensitive and evolving but going well, and after a pause Lelia said down to her cold plate, Oh good, it’s the Henryspeak.

By then she had long known what I was. For the first few years she thought I worked for companies with security problems. Stolen industrial secrets, patents, worker theft. I let her think that I and my colleagues went to a company and covertly observed a warehouse or laboratory orretail floor, then exposed all the cheats and criminals.

But I wasn’t to be found anywhere near corporate or industrial sites, then or ever. Rather, my work was entirely personal. I was always assigned to an individual, someone I didn’t know or care the first stitch for on a given day but who in a matter of weeks could be as bound up with me as a brother or sister or wife.

I lied to Lelia. For as long as I could I lied. I will speak the evidence now. My father, a Confucian of high order, would commend me for finally honoring that which is wholly evident. For him, all of life was a rigid matter of family. I know all about that fine and terrible ordering, how it variously casts you as the golden child, the slave-son or -daughter, the venerable father, the long-dead god. But I know, too, of the basic comfort in this familial precision, where the relation abides no argument, no questions or quarrels. The truth, finally, is who can tell it.

And yet you may know me. I am an amiable man. I can be most personable, if not charming, and whatever I possess in this life is more or less the result of a talent I have for making you feel good about yourself when you are with me. In this sense I am not a seducer. I am hardly seen. I won’t speak untruths to you, I won’t pass easy compliments or odious offerings of flattery. I make do with on-hand materials, what I can chip out of you, your natural ore. Then I fuel the fire of your most secret vanity.”

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

De Filipijnse dichter en letterkundige J. Neil C. Garcia werd geboren in 1969 in Manilla. Zie ook alle tags voor J. Neil C. Garcia op dit blog.

Uit: Poems from Amsterdam (Fragment)

XXXV

Of course, I know the strategy:

to enfold the moment in sound,

earmark it with rhythm, file it

into the mind with the textures,

syncopations, and airs of a song.

Julius, visiting the lovely De Krijtberg

and its goldleafed nave and altarpiece,

its stained glass, the saints poised delicately

under tiered canopies carved into the walls,

the woodsy scent of incense, tapers softly lit

at the foot of a smiling Madonna and Child—

made sure his iPod played a tune

with which to brand the experience

dark against his memory’s milky skin.

Thus tethered, it can thereafter

be summoned at the merest whim:

nostalgia triggered by the mood

deliberately chosen noise calls forth.

He’s since recurred to his adopted Canberra

where, he writes, it’s bitterly cold these days.

I can almost see him plugging into his machine,

to bask in vicarious, melodic warmth.

Astonishingly enough, here, with me,

it’s no different. Late-night TV in this city

is a redundancy of “quick sex” commercials:

Red-Light women moaning lekker,

an all-purpose Dutch word, it would appear,

for anything nice, delicious, tempting, or great,

in between puckering up, licking a fat dildo,

stroking their breasts with pink-tipped fingers,

and rearing their scantily clad haunches

up at the camera’s snoopy gaze.

It was interesting the first few seconds, but

not much after that. Luckily, a music channel

called The Box plays purely “classic” stuff.

A veritable box of found memories:

videos dusted off from the eighties

by singers and bands with overblown hair,

silly repeating lyrics, and outlandish makeup,

especially around the fiery lips and eyes—

the sights and sounds of my own salad days.

Which is to say: high school, arguably

the best episode, thus far, in my uneventful life,

steeped in brash fun with like-minded friends.

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 29e juli ook mijn blog van 29 juli 2018 en ook mijn blog van 29 juli 2017 deel 1 en ook deel 2.