De Engelse dichter en vertaler Jamie McKendrick werd op 27 oktober 1955 in Liverpool geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Jamie McKendrick op dit blog.

A Mole of Sorts

The digging creature has been at work again

out there — first a modest trough with a crest

of dry earth, fit for a starling or a thrush

to rest in. No big deal except to some yellow ants

doing repairs, carrying stuff on their hods.

Next day the hole was deeper,

deeper and wider, encroaching on the lawn

which yielded inch by inch each clump of turf

as though to a pendulum or scythe.

Asleep, I sat talking to an animal:

three-, four-foot long with silky white fur

and slim interminable fingernails

lucid as biro shafts or goose quills.

They made the plasticky click

of knitting needles as he waved them

in front of his pink snout as if to dry

the shining varnish. He was indeed

he declared to me a mole of sorts.

In a question of days, two weeks at most,

the lavender, the rose bush, the bay plant,

the bindweed, the lilac tree, the brambles

and the potato vine had disappeared

leaving a long rectangular pit

like the foundations of a house

that would never be built, never be lived in.

Then I suppose that was the job done

and the digger moved on to another plot

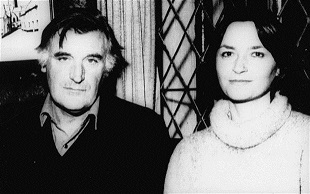

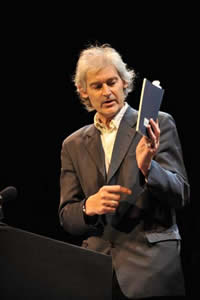

Jamie McKendrick (Liverpool, 27 oktober 1955)

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Frances Ann “Fran” Lebowitz werd geboren op 27 oktober 1950 in Morristown, New Jersey. Zie ook alle tags voor Frans Lebowitz op dit blog.

Uit: Fran Lebowitz Doesn’t Have a Cell Phone, But Knows Everything That Happens on Social Media Anyway (Interview door Stephanie Eckardt op W Magazine)

“Have you read any new novelists lately that you’re excited about?

By new novelists you probably mean people right out of writing school, which didn’t use to exist. I mean, it’s not that I’m against the idea of new novelists. I’m always asking people if they’ve read anything new that is really good. They very rarely say yes, and when they do, they’re often wrong. My idea of a new novelist is someone who’s still alive. I read Darryl Pinckney’s novel, Black Deutschland. I’m sure he’s not your idea of young, but he’s younger than me. That might be the most recent novel I read by someone who’s alive.

What about by someone who’s not?

My great preference. You know what, I just read Little Dorrit, because I asked a friend of mine what she recommended and she said “Did you ever read Little Dorritt?” And I said, “I think I did not,” because when I was young, I was not the world’s biggest [Charles] Dickens fan. So I did read it, and I would highly recommend it, and he is definitely not alive. The great thing about writers who are not alive is that you don’t meet them at parties.

Do you watch any TV shows?

I watch TV all night long, I flip it on and off. But I have to tell you that watching TV is really an exact description, by which I mean if something interests me I’ll watch it ’til the commercial, then I’ll flip and I don’t even remember that I watched it anymore. I know this is against the law, but I am also the only person I know of who is not presently obsessed with television. I never imagined that I would live to see a day where people talked about television all the time. I’m astounded by the number of people who — do you realize how much TV you’re watching? Thousands of hours. Thousands of hours. And people now think it’s like a requirement. I have to go, I have 75 episodes of such and such I have to watch. I’m not saying these shows are not good, I’m just saying maybe if I was three years old and I imagined I had this amount of time ahead of me, I might start pursuing it.

Do you have cable?

I do. When they first invented cable television, I didn’t get it. I thought it was ridiculous to pay to watch television. It should be free, like water. [Laughs.] I didn’t get it until they built the World Trade Center (I mean the initial one) because that cut off the TV reception to downtown. So I do have cable television.”

Fran Lebowitz (Morristown, 27 oktober 1950)

De Tsjechische schrijver, dichter, journalist en vertaler Josef Václav Sládek werd geboren op 27 oktober 1845 in Zbiroh. Zie ook alle tags voor Josef Václav Sládek op dit blog.

We’ll Last, As We’ve Lasted

We’ll last, as we’ve lasted

up till now, awoken,

though fate-battered, blasted,

never crushed or broken.

Many tidal surges

at our promontory

fought off down the ages,

we’ll fight on, yield nary!

Though our flags be rended,

rooftop torn, storm-blustered,

we’ll stay, our house tended

by our hands, own-mastered.

Let seas seethe, rapacious,

by our blood outlasted,

gutsy, contumacious,

we’ll last, as we’ve lasted!

Vertaald door Václav Z J Pinkava

Josef Václav Sládek (27 oktober 1845 – 28 juni 1912)

De Britse schrijfster Enid Algerine Bagnold werd geboren op 27 oktober 1889 in Rochester, Kent. Zie ook alle tags voor Enid Bagnold op dit blog.

Uit: A Diary Without Dates

“When one shoots at a wooden figure it makes a hole. When one shoots at a man it makes a hole, and the doctor must make seven others.

I heard a blackbird sing in the middle of the night last night – two bars, and then another. I thought at first it might be a burglar whistlingto his mate in the black and rustling garden.

But it was a blackbird in a nightmare.

Those distant guns again tonight…

Now a lull and now a bombardment; again a lull, and then batter,batter, and the windows. Is the lull when they go over the top?

I can only think of death tonight. I tried to think just now, ‘What is it, after all! Death comes anyway; this only hastens it.’ But that won’tdo; no philosophy helps the pain of death. It is pity, pity, pity, that I feel, and sometimes a sort of shame that I am here to write at all.

Summer… Can it be summer through whose hot air the guns shakeand tremble? The honeysuckle, whose little stalks twinkled and shone that January night, has broken at each woody end into its crumbled flower.

Where are the frost, the snow? … Where are the dead?

The sound of a bombardment at the Front, which could be heard in England.

Where are my trouble and my longing, and the other troubles, and the happiness in other summers?

Alas, the long history of life! There is that in death that makes the throat contract and the heart catch: everything is written in water.

We talk of tablets to the dead, there can be none but in the heart, and the heart fades.”

Enid Bagnold ( 27 oktober 1889 – 3 maart 1981)

De Poolse schrijver Kazimierz Brandys werd geboren op 27 oktober 1916 in Lodz. Zie ook alle tags voor Kazimierz Brandys op dit blog.

Uit: Maanden (Vertaald door Liesbeth Schnack-Dijkhuis)

“November 1978

Honderd passen van mijn poortdeur. Al twintig jaar blijven daar groepen buitenlandse toeristen even staan, al twintig jaar hoor ik diezelfde hese bariton: ‘That is the old gothic door of fifteenth century!’ Daarop weerklinkt het toeristisch gekakel, de groep bekijkt mijn poort. Sinds twintig jaar vervloek ik dat wezen en haat ik zijn heesheid. Pas een maand geleden heb ik, op weg naar huis, die gids voor het eerst gezien. Het was een vrouw, al wat ouder, met donkere, lachende ogen, waarmee ze me niet zonder sympathie een steelse blik toewierp, alsof ze mijn langjarige kwellingen begreep. Haar schoenen zaten onder de modder. Ik voel sindsdien geen haat meer als ik haar bariton beneden hoor. Op honderd passen van mijn poort gebeuren wonderen. Niet overdrachtelijk, nee, echte wonderen, met een wonderdoener die uit Engeland is gekomen. Tussen het Bastion en de Swietojerskastraat staat al sinds vroeg in de ochtend een menigte. Mensen op karretjes, mannen met kinderen op de arm, grijsaards, verlamde vrouwen, zonen die hun moeders in rolstoelen voortduwen, een hoop mensen met een schijnbaar gezond uiterlijk, veel jonge gezichten. De zijstraten zijn aan het eind versperd met auto’s, er komen ziekenauto’s aangereden. De menigte staat uren te wachten, om de zoveel tijd klinkt er aan de voet van de Heilige-Jacekkerk een megafoon die nummers en namen afroept. De healer, Clive Harris, geneest door handoplegging. De zieken schuiven ieder op hun beurt naar voren, er is een stem van een vrouwelijke tolk te horen: ‘Head… Leg… Breast…’ De healer, zijn ogen halfdicht, beroert hoofden, armen, borsten. Naar het schijnt neemt hij de pijn weg en doet zijn aanraking gezwellen wijken. Harris is een veertigjarige man, kort van gestalte, met kleine handen en voeten; hij heeft iets ziekelijks over zich, een soort kreupele jongensachtigheid. Hij beroert de zieken als in trance. De header uit roeping straalt – naar ik heb gehoord – elektromagnetische golven uit. Om de paar uur drinkt hij twee, drie bekers melk. De wonderen berusten ook op belangeloosheid. Harris neemt geen geld aan.

Over dat alles vertelde mevrouw Helenka, die op haar reumatische benen even bij ons langs was gekomen om uit te rusten nadat ze vijf uur in de menigte had gestaan. Ontdaan kwam ze binnen, een zilvervos aan, een vilten, roestbruine baret op het hoofd en ringen in de oren. Ze werkt nu al acht jaar niet meer bij ons, maar twintig jaar lang heeft ze bij ons gediend, na de oorlog aanbevolen door mevrouw Bronia, de vroegere huishoudster van tante Klima Heyman, de overleden zuster van mijn moeder. Ik schoof mijn werk opzij om wat met haar te praten. We hadden het over ziektes, over mensen die overleden waren, over de duurte.”

Kazimierz Brandys (27 oktober 1916 – 11 maart 2000)

Cover

De Iraanse schrijver en filmmaker Reza Allamehzadeh werd geboren op 27 oktober 1943 in Sari, Mazandaran. Zie ook alle tags voor Reza Allamehzadeh op dit blog.

Uit: Steril und illusorisch. Iranische Erfahrungen mit dem „islamischen Kino“

“Vierzehn Jahrhunderte nach Erscheinen des Propheten hat es die islamische Revolution im Iran auf sich genommen, endlich das heilige Bilderverbot des Koran durchzusetzen. Mit zu den ersten Aktionen der damals noch jungen Bewegung gehörte das Abbrennen von Kinos in Teheran und anderen Städten. Die Brandstiftungen erreichten im September 1978 einen Höhepunkt, als das „Rex“ im südiranischen Abadan von religiösen Fanatikern und Khomeini-Anhängern angezündet wurde; sie verschlossen alle Ausgänge des mit 400 Menschen besetzten Kinosaales und legten Feuer. Von den 400 Männern, Frauen und Kindern, die sich dort eingefunden hatten, um einen iranischen Film zu sehen, verbrannten 377 bei lebendigem Leibe. In diesem Kontext sah das iranische Kino der Ankunft der islamischen Revolution entgegen.

Nach seinem Machtantritt 1979 ließ sich Khomeini von engen Beratern überreden, zwei Filme des in den USA lebenden arabischen Regisseurs Mostafa A’ghad anzusehen; beide Filme, The Messenger und Omar Mokhtar, sind Beispiele für aufwendige Hollywoodproduktionen, in denen ein islamisches Thema im Zentrum steht. Wenig später machte Khomeini eine seiner obskuren und orakelhaften Äußerungen, die seinen Ruf als unbestrittener Meister der Doppeldeutigkeiten begründeten: „Wir sind nicht gegen das Kino, wir sind gegen Prostitution.“ Seit diesem Tag versucht die iranische Filmindustrie herauszufinden, was genau der Meister damit gemeint haben könnte. Die orthodoxe Auffassung ist simpel genug: „Wir sind gegen das Kino, weil es Prostitution ist.“ Der zur Zeit gültige Trend in den Regierungsinstitutionen, die die Filmindustrie kontrollieren, läßt den Satz folgendermaßen interpretieren: „Wir sind gegen die Art von Kino, die Prostitution bedeutet, nicht aber gegen ein islamisches Kino.“ Das islamische Regime hat einige Jahre gebraucht, um zu erkennen, daß die Konzeption eines islamischen Kinos illusorisch ist.

Der Direktor der Kulturabteilung in einer der größten Regierungsstellen „für islamische Filmproduktion“, Mohsen Tabatab’i, hat erklärt: „Die beste Definition des islamischen Kinos besagt, daß das Kino in der Propagierung des Islam eine eigene Rolle zu spielen hat — so wie auch die Moschee ihre Aufgabe hat.“ Um dieses Ziel zu erreichen, gibt die Filmstiftung jährlich 25 bis 40 Millionen US-Dollar aus — „zur Förderung des neuen islamischen Films“. Die „Bonyad-e-Mostafazan“ („Stiftung der Schwachen“) besitzt etwa 80 Prozent aller iranischen Kinos.”

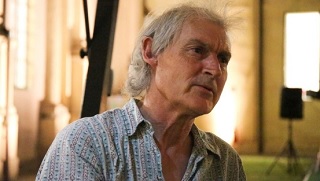

Reza Allamehzadeh (Sari, 27 oktober 1943)