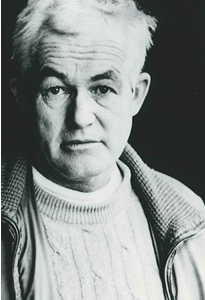

De Israëlische schrijver Etgar Keret werd geboren op 20 augustus 1967 in Ramat Gan. Zie ook alle tags voor Etgar Keret op dit blog.

Uit: The Nimrod Flipout: Stories (Vertaald door Miriam Shlesingeren Sondra Silverston)

“Surprised? Of course I was surprised. You go out with a girl. First date, second date, a restaurant here, a movie there, always just matinees. You start sleeping together, the sex is mind-blowing, and pretty soon theres feeling too. And then, one day, she shows up in tears, and you hug her and tell her to take it easy, everythings going to be OK, and she says she cant stand it anymore, she has this secret, not just a secret, something really awful, a curse, something shes been wanting to tell you from the beginning but she didnt have the guts. This thing, its been weighing her down, and now shes got to tell you, shes simply got to, but she knows that as soon as she does, youll leave her, and youll be absolutely right to leave her, too. And then she starts crying all over again.

I wont leave you, you tell her. I wont. I love you. You try to look concerned, but youre not. Not really. Or rather, if you are concerned, its about her crying, not about her secret. You know by now that these secrets that always make a woman fall to pieces are usually something along the lines of doing it with an animal, or a Mormon, or with someone who paid her for it. Im a whore, they always wind up saying. And you hug them and say, no youre not. Youre not. And if they dont stop crying all you can do is say shhh. Its something really terrible, she insists, as if shes picked up on how nonchalant you are about it, even though youve tried to hide it. In the pit of your stomach it may sound terrible, you tell her, but thats just acoustics. As soon as you let it out it wont seem anywhere near as bad youll see. And she almost believes you. She hesitates and then she asks: What if I told you that at night I turn into a heavy, hairy man, with no neck, with a gold ring on his pinkie, would you still love me? And you tell her of course you would. What else can you say? That you wouldnt? Shes just trying to test you, to see whether you love her unconditionally and youve always been a winner at tests.”

Etgar Keret (Ramat Gan, 20 augustus 1967)