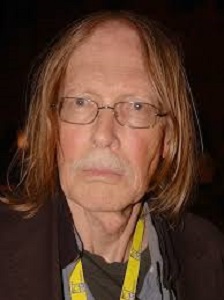

De Amerikaanse schrijver, muzikant en songwriter Willy Vlautin werd geboren op 7 november 1967 in Reno, Nevada. Hij was leadzanger, gitarist en songwriter van de rockband Richmond Fontaine (1994-2016) en is momenteel lid van The Delines. Hij heeft sinds het midden van de jaren negentig elf studioalbums uitgebracht met Richmond Fontaine, terwijl hij vijf romans schreef. Het werken als zowel songwriter als romanschrijver biedt Vlautin een mechanisme om dezelfde personages en situaties te ontwikkelen in zowel zijn songs als in zijn boeken. De hoofdrolspeler in Northline (zelf een nummer van het Winnemucca-album van Richmond Fontaine) is Allison Johnson. “Allison Johnson” was de titel van een nummer op hun album “Post to Wire”. Vlautins eerste boek “The Motel Life” werd in 2005 uitgegeven en is sindsdien in elf talen vertaald. In “The Motel Life” vertelt Vlautin het verhaal van twee broers die in een hotel in Reno wonen. Hij verwierf de titel van “Dylan of the dislocated “(The Independent). “The Motel Life” werd verfilmd in 2012. “Northline” was het tweede boek van Vlautin. De serveerster Allison Johnson vertrekt vanuit Las Vegas naar Reno om een nieuw leven te beginnen. Een CD met instrumentale en droevige liedjes van Richmond Fontaine is opgenomen in de eerste editie van het boek. In 2008 bracht Vlautin zijn eerste CD met gesproken woord uit, A Jockey’s Christmas, een zwarte komedie over een te zware, alcoholische jockey die voor de feestdagen naar huis gaat in Reno. De derde roman van Vlautin, “Lean on Pete”, is het verhaal van een 15-jarige jongen die werkt en leeft op een vervallen racecircuit in Portland, Oregon, en bevriend raakt met een mislukt racepaard genaamd “Lean on Pete”. Voor het boek ontving de schrijver in 2010 de Ken Kesey Award voor fictie en literaire kunst en de Oregonian People’s Choice Award. In zijn vierde roman “The Free” vertelt Vlautin over Leroy Kervan, een suïcidale Irak-veteraan.

Uit: The Motel Life

“The night it happened I was drunk, almost passed out, and I swear to God a bird came flying through my motel room window. It was maybe five degrees out and the bird, some sorta duck, was suddenly on my floor surrounded in glass. The window must have killed it. It would have scared me to death if I hadn’t been so drunk. All I could do was get up, turn on the light, and throw it back out the window. It fell three stories and landed on the sidewalk below. I turned my electric blanket up to ten, got back in bed, and fell asleep. A few hours later I woke again to my brother standing over me, crying uncontrollably. He had a key to my room. I could barely see straight and I knew then I was going to be sick. It was snowing out and the wind would flurry snow through the broken window and into my room. The streets were empty, frozen with ice. He stood at the foot of the bed dressed in underwear, a black coat, and a pair of old work shoes. You could see the straps where the prosthetic foot connected to the remaining part of his calf. The thing is, my brother would never even wear shorts. He was too nervous about it, how it happened, the way he looked with a fake shin, with a fake calf and foot. He thought of himself as a real failure with only one leg. A cripple. His skin was blue. He had half-frozen spit on his chin and snot leaking from his nose. `Frank,’ he muttered, ‘Frank, my life, I’ve ruined it.’ `What?’ I said and tried to wake. `Something happened.’ `What?’

`I’m freezing my ass off. You break the window?’ `No, a duck smashed into it.’ `You kidding?’ `I wouldn’t joke about something like that.’ `Where’s the duck then?’ `I threw it back out the window.’ `Why would you do that?’ `It gave me the creeps.’ `I don’t even want to tell you, Frank. I don’t even want to say it. I don’t even want to say what happened.’ `You drunk?’ ‘ Sorta.’ `Where are your clothes?’ `They’re gone.’ I took the top blanket off my bed and gave it to him. He wrapped it around himself then plugged in the box heater and looked outside. He stuck his head out the broken window and looked down. `I don’t see a duck.’ `Someone probably stole it.’ He began crying again. `What?’ I said. `You know Polly Flynn, right?’

`Sure.’ I leaned over and grabbed a shirt on the floor and threw up into it. `Jesus, you okay?’ `I don’t know.’ `You want a glass of water?’ `No, I think I feel a little better now.’ I lay back in bed and closed my eyes. The cold air felt good. I was sweating, but my stomach began to settle. `I’m glad I don’t puke at the sight of puke.’ `Me too,’ I said and tried to smile. ‘What happened?’ `Tonight she got mad at me,’ he said in a voice as shaky as I’ve ever heard. ‘I don’t remember what I said, but she yelled at me so hard that I got up to get dressed but she got up first and took my pants and wouldn’t give them back. She ran outside and set fire to them with lighter fluid.”

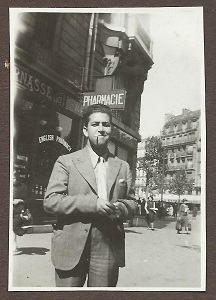

Willy Vlautin (Reno, 7 november 1967)