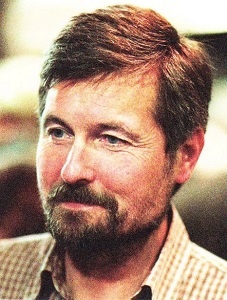

De Poolse schrijver en literair historicus Stefan Chwin werd geboren op 11 april 1949 in Gdansk. Chwin is een afstammeling van Litouwse Polen, die na de Tweede Wereldoorlog uit Litouwen werden verdreven. Zijn vader werd geboren in Vilnius en kwam in 1945 in een volledig verwoest Gdańsk terecht. Chwin volgde een opleiding aan de kunstacademie in Gdynia en studeerde Poolse taal- en letterkunde aan de universiteit van Gdańsk. Later promoveerde hij in de Poolse taal en letterkunde en sinds 1998 is hij hoogleraar in dit vak. Zijn voornaamste interesse als literatuuronderzoeker is de Poolse romantiek en de invloed ervan op moderne schrijvers. Hij heeft verschillende boeken gepubliceerd met literaire studies over auteurschap en tendensen in de Poolse literatuur. Chwin zat ook in de redactie van verschillende Poolse literaire tijdschriften. Chvin’s werken zijn vertaald in twaalf verschillende talen. In de jaren tachtig deed Stefan Chwin zijn eerste poging als schrijver van fictie. Hij debuteerde met twee avonturenboeken voor kinderen onder het pseudoniem Max Lars.Zijn doorbraak als schrijver voor volwassenen was de verschijning van de roman “Hanemann” in 1995, waarvoor hij de Paszport Polityki, een Poolse cultuurprijs, ontving.In 1999 verscheen de roman “Esther”, gevolgd in 2003 door “Złoty pelikan“ (De gouden pelikaan). Verschillende romans spelen in de geboorteplaats van de auteur, Gdańsk, en thematiseren op verschillende manieren de multiculturele geschiedenis van die stad. Gdańsk was tot 1945 vooral Duitstalig onder de naam Danzig, toen de Duitse bevolking werd verdreven en vervangen door Polen, die werden verdreven uit de oostelijke grensregio’s van Polen. De belangstelling voor de Duits-Poolse geschiedenis van de stad deelt hij met een andere vooraanstaande schrijver uit Gdańsk, Paweł Huelle.

Uit: Death in Danzig (Hanenemann, Vertaald door Philip Boehm)

“When Hanemann reached the gate in front of his house, he thought he saw a light flickering at Lessingstrasse 14, the house owned by the Bierensteins. He walked past the arborvitae and turned and crossed the street. He pushed open the heavy doors and stepped into the entrance hall, automatically scraping the snow off his feet on the iron grate. He struck a match and held it up until it singed his fingers. The little yellow flame wavered in the chilly darkness and went out. Hanemann wondered why he had come, if he was merely trying to assuage his heart—but what difference did it make now? Still, he had seen that light … He wanted to go back to Number 17, through the double row of arborvitae to his own door, and he would have done so if he could have stopped thinking about the landing in Neufahrwasser, that white space between the warehouse and the brick wall round the yard. The scraps of paper, the black smudges in the snow, the landing, the suitcases, the crowd, the piles of clothing, the shouts, the gentle voice of Mrs Walmann. That was what kept him from leaving, what stopped him there, on the stairs, in the dark entry hall under the oval window, where the coloured panes muted the glare over Langfuhr into a feeble glow. Here, on the right—the Schultzes’ apartment. He dragged another damp match across the edge of the box, there was a sulphurous flash, and he held the match high against the brown panelling, his palm cupped pink around the tiny flame. The darkly varnished door, with the floral ornamentation on its oak frame, glinted and glistened in the flickering light. Above it, a stucco relief emerged from the shadows that slanted across the wall—a Madonna and Child, nestled within a wreath of olive branches. But what he saw next … deep gashes and gouges on the Schultzes’ door, right along the jamb. Flashing bits of broken metal round the latch housing.

Fresh yellow scratches, black dents and bruises, as if someone had tried to pierce the brass with a knife. So they’re already here, they’ve already been here; while he waited by the waterfront at Neufahrwasser, they had been breaking into an apartment on Lessingstrassc, cursing under their breath as they grappled with the brass reinforcement, as they pried at the metal escutcheon beneath the latch before finally ramming the door with their shoulders and bursting inside, struggling to keep their balance on the slick linoleum with the white and yellow checkerboard pattern. He wanted to go back home, to avoid the sight of the ransacked wardrobes, the huge heaps of linens dragged off the shelves, the drawers ripped out of the chest and tossed into the middle of the room, the rug trampled by muddy boots and stained with clods of melting snow. But the thought of the Schultzes … They had left at noon; he’d watched them turning onto Kronprinzenallee, just beyond the chestnut trees. Otthter with a little rucksack. A stroller. A wooden suitcase. Mrs Schultz’s red hat. She had turned round. A brief glance at the building…. Hanemann grabbed the handle; the door yielded softly to his hand. Dark-red door curtains in the entry room. Tea-coloured wallpaper. Shadows. The match went out, he groped his way towards the kitchen, something crunched beneath his soles. When he could see the window—its rectangle glowing dimly in the dark, the thin cross of its frame—he again reached for a match.”

Stefan Chwin (Gdansk, 11 april 1949)