De Iraanse schrijfster Shahrnush Parsipur werd geboren op 17 februari 1946 in Teheran. Zie ook alle tags voor Shahrnush Parsipur op dit blog.

Uit: Touba and the Meaning of Night (Vertaald door Kamran Talattof and Havva Houshmand)

“Haji Adib thought, “I am old.” His heart sank. There was not much time left to spend on the subject of becoming and metamorphosis, or the spirit of dust in part and whole, or to contemplate the trees as a whole or the minute parts making up the whole. He thought that probably each in its own minute society had a few Haji Adibs and Moshir O’Dolehs and Englishmen who fought each other. He laughed and imagined that probably Asdolah their local butcher chopped their meat for them. And then he laughed loudly again.

Suddenly the rhythmic sound of the shuttle comb stopped in the basement. Haji Adib could no longer hear the soft conversations of the women. The sun had not yet reached the middle of the sky. Haji Adib still sat on the edge of the octagonal pool, his fist under his chin. He turned his head around and, through the sharp angle that formed between his head and his arm, looked in the direction of the basement. The women had gathered by the basement window staring in his direction and were whispering. He had a feeling that they were talking about him. He remembered that just a few seconds ago he had laughed, loud and without inhibition, in a manner that was not appropriate to his position, and that the women had never seen such behavior in him. As he slowly tapped his foot on the ground, he thought, “They think. Unfortunately, they think. Not like the ants nor like the minute parts of the tree, nor like the particles of dust, but more or less as I do.” But, he was certain that they would never have thoughts about Mullah Sadra.

Suddenly he was shaken again, for of course they could think about Mullah Sadra as well. Had that not been the case with that rebellious and audacious woman who lived in their town when he was a child, who created all that uproar and sensation? People said that she was a prostitute, but they also said that she was learned. How much talking there was about her! He remembered someone telling his father that she was the messiah. The women were laughing behind the basement window. Haji thought disparagingly that they were behaving with typical women’s foolishness. One pushed and the others burst out laughing; one was tickled while the other tried to get away. If there had not been a man in the house, their laughter would probably have been heard all over. Undoubtedly some of them were going crazy for not having a husband, but it was not possible to find husbands for them. They were dependent on Haji Adib, and there was not a man available at the moment who was rich enough to take one of them. Besides, if they did get married who would then weave the carpets? For that, he couldn’t bring strange women into the house. They might then participate in some perverse activities with one another.”

Shahrnush Parsipur (Teheran, 17 februari 1946)

Cover

De Nederlandse dichter Willem Thies werd geboren op 17 februari 1973 in Nijmegen. Zie ook alle tags voor Willem Thies op dit blog.

De onmacht van Michelangelo

De wind neemt happen van het gras.

Iemand legt bloemen op een onbemand graf.

Een wit kind wuift met een wijde arm

en begint stil te zingen.

Een reepje stof hangt omlaag

van de stomp van een tak.

De wind haalt zijn hand door het gras.

Tandeloze kam.

Een bij harpoeneert mijn arm

en verliest lijf en leven.

Zoals eenieder die tot in de kern

tracht door te dringen,

in de huid steken blijft.

Er is een steen die men niet vormen kan naar zijn hand.

De gastvrije doden

Dennenappels. Boeketten. Prenten

met punaises op een boom geprikt.

Een man prevelt voor een naam met jaren,

aan zijn voeten groeit een schaduw.

Een hoed ligt op het hoofdeinde

van eengraf, in de deuk staat regenwater.

Het muurtje rondom neemt laag

na laag af, de toegang gevormd

door een enkele rij stenen,

om de levenden door te laten.

Mezen buitelen dor de lucht of

pikken pinda’s van een snoer.

Mensen stampen aarde

uit het profiel van

hun schoenzolen om

op de parkeerplaats

achter te laten.

Willem Thies (Nijmegen, 17 februari 1973)

De Iraanse schrijver Sadegh Hedayat werd geboren op 17 februari 1903 in Teheran. Zie ook alle tags voor Sadegh Hedayat op dit blog.

Uit: The Silent Language of a Donkey at the Time of Death (Vertaald door Farzin Yazdanfar)

“But all these words have produced no results because of the lack of a law for preventing and limiting human beings’ cruelty and their limitless cupidity and avidity. If my legs had been crushed in the West, I would have been relieved from this futile suffering or they would have put me to sleep! Ah! Save me from the pain and hunger! I wish I were free to live among animals of my own kind in pastures with a nice climate and to die on the day determined by my destiny. But now I am dying of hunger and hardship in captivity. This is the awful consequence of the life of a speechless animal who has been enslaved by this two-legged creature. I have to burn in the fire that they have kindled. Ah! My patience has reached its limits…! Human beings are killers of the oppressed. Why don’t they take untamed and rapacious animals into captivity and put them in service? The only sin that we, tamed animals, have committed is the fact that we are harmless and deprived of our daily food.

The world has become dark and murky before my eyes. My body has grown feeble from the suffering inflicted on me by hunger. I can hear somebody’s footsteps. Perhaps this is my master who is feeling sorry for my unhappiness and bringing me food. No, it is just a kid who throws a stone at me and runs away.

The sooner I die the sooner I will be able to take vengeance from this cruel tyrant before the court of eternal justice.”

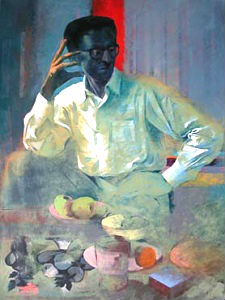

Sadegh Hedayat (17 februari 1903 – 9 april 1951)

Portret door Amin Nourani, 2004

De Russische schrijver, regisseur en acteur Yevgeni Grishkovetz werd geboren op 17 februari 1969 in Kemerovo. Zie ook alle tags voor Yevgeni Grishkovetz op dit blog.

Uit: How I Ate the Dog

“I’ll talk about a person who is no more now, who already doesn’t exist, in the sense that he existed before, but now he ceased to exist, but besides me no one noticed this. And when I reminisce about him or talk about him, I say, “I thought… or I said”…. And I remember all this in detail, what he did, how he lived, what he thought, I remember why he did this or that, well, good thing, or, more often, bad thing…. I even become embarrassed for him, even though I distinctly understand that it wasn’t me. No, not me. In the sense that for everyone who knows me and knew me it was me, but actually that “I” who’s now saying this is a different person, and that one is no more and has no chance of appearing again…. In short, I ended up having to serve three years in the Pacific fleet…. That’s what kind of person this was.

(…)

I remember how we traveled seven days from the “Taiga” station to the Vladivostok station on a passenger/mail train. We traveled slowly, stood at each crossing, and I was grateful to the railroad workers for these tiny delays…. We were going…, and interestingly, you could be going anywhere, to the east, to the south, to the north, and the whole time it would be the exact same scenery, in the sense that, it changes, of course, but the feeling remains that it’s the exact same: This means not very thickly growing birch trees, those uniformly spaced white-black trees, everywhere…. Well, in general, the kind of scenery, looking at which a Russian is obligated to say: “My God… what beauty!” It happens like this: The Russian has woken up, comes out from the sleeping compartment into the corridor of the wagon, on his shoulders hangs a towel, like so, in his hand a toothbrush with toothpaste already on it, he’s a bit blinded by the morning light (in the compartment it had been very dark), he stops at the window, like so, holding onto the handrail. In the corridor the rattle of the train is stronger. Someone draws water from the tea urn. The train: tuduk-tuk-tuk, tuduk-tuk-tuk. The person who has just woken up: “Ssssoooo, where are we by now?” The person with hot water in his mug, swaying with concentration, slowly walking and because of this swaying even more, says: “Who knows…”

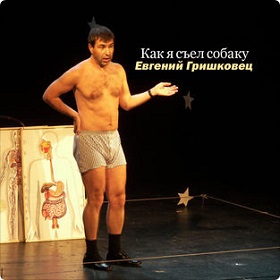

Yevgeni Grishkovetz (Kemerovo, 17 februari 1969)

Cover

De Nederlandse schrijver Albert Kuyle werd geboren in Utrecht op 17 februari 1904. Zie ook alle tags voor Albert Kuyle op dit blog.

Uit: Harten en Brood

“En Jansen doet heelemaal niets. Die zit maar op een gematte stoel, met zijn kousevoeten op de sport van een andere. Hij heeft alles gezien wat er te zien is, en hij kijkt nog. De zonnebloem die voorover hangt van zwaarte, de drie broeken aan de lijn die slap hangen van vocht.

Van Duin loopt nu door de emballage-afdeeling. Hij blijft even staan bij de man die bandijzer om de kisten legt. Pootige kerel. Vlugge werker. De chef hier is een halve gare, die met een hoog boord om werkt. Hij heeft iets krampachtig heerachtigs over zich. Het schijnt dat hij voorzitter is van verschillende vereenigingen en in het bestuur van de leeszaal zit. Hier doet hij in ieder geval niets dan bonnen schrijven en toekijken en zenuwachtig worden als er op het kantoor een reclame is over onvoldoende verpakking en beschadigde zending.

Hij neemt zijn groene hoedje af voor mijnheer. Dat draagt hij voor de tocht, en hij zet het af uit eerbied. Het remt echter de kruistocht van van Duin niet. Die loopt door en hij komt bij de getouwen. Als hij binnenkomt, hoort hij slordig een ‘meneer’ mompelen, tusschen het krakende gezoem van de machines door. Het is de kortste en minst zeggende groet die men kan bedenken. Het beteekent evenzeer ‘goeje morgen’ als ‘stik de moord’, en van Duin mag het zelf uitzoeken. Het deert hem niet. Dit is altijd zijn beste uur van de dag. Als hij het flikkerend zweven van de wielen ziet, het wazig flimmeren van de riemen en hij ziet hoe de stof tot een vast geheel wordt.

Hij staat tusschen de coulissen, en hij bewondert het spel. Ja, zooveel van de eerlijke sportman steekt er nog in hem, dat hij werkelijk het spel bewondert. En dat is gelukkig, want het filtert veel beroerde dingen in hem. Een man die veel te weinig wordt tegengesproken, een man die iederen dag goed eet, een man die zijn lusten heeft bevredigd zonder stagnatie, een man die om-en-de-bij nooit echt bidt, zoo’n man groeit natuurlijk geestelijk krom en scheef. Er komt een driftprop in zoo’n kerel, die maar een klein zetje noodig heeft om als een kogel er uit te vliegen. Dit, dit gelijkmatig bewegen van menschen en machines, daar kan hij niet tegen op. Hij heeft hier niet het gevoel dat hij dat maakte, dat hij dat beheerscht. Hij heeft hier een zeker ontzag, een vreemde eerbied, voor de dingen en voor de kracht. Hij is de bewaker ervan, van deze religie, van deze tempel en hij doet zijn werk van toekijken en bewonderen schuchter en onopgemerkt.

Albert Kuyle (17 februari 1904 – 4 maart 1958)

Cover

De Tsjechische dichter en schrijver Jaroslav Vrchlický (eig. Emilius Jakob Frida) werd geboren op 17 februari 1853 in Louny, Bohemen. Zie ook alle tags voor Jaroslav Vrchlický op dit blog.

To Be A Poet

Life taught me long ago

that music and poetry

are the most beautiful things on earth

that life can give us.

Except for love, of course.

In an old textbook

published by the Imperial Printing House

in the year Vrchlickys death

I looked up the section on poetics

and poetic ornament.

Then I placed a rose in a tumbler,

lit a candle

and started to write my first verses.

Flare up, flame of words,

and soar,

even if my fingers get burned!

A startling metaphor is worth more

than a ring on ones finger.

But not even Puchmajers Rhyming Dictionary

was any used to me.

In vain I snatched for ideas

and fiercely closed my eyes

in order to hear that first magic line.

But in the dark, instead of words,

I saw a womans smile and

wind-blown hair.

That has been my destiny.

And Ive been staggering towards it breathlessly

all my life.

Vertaald door Ewald Osers

Jaroslav Vrchlický (17 februari 1853 – 9 september 1912)

Portret door Hynais Vojtech. z.j.

De Amerikaanse schrijver Chaim Potok werd geboren in New York City op 17 februari 1929. Zie ook alle tags voor Chaim Potok op dit blog.

Uit: The Chosen

“Throughout the warm-up period, with only our team in the yard, he kept thumping his right fist into his left palm and shouting at us to be a solid defensive front.

“No holes,” he shouted from near home plate. “No holes, you hear? Goldberg, what kind of solid defensive front is that? Close in. A battleship could get between you and Malter. That’s it. Schwartz, what are you doing, looking for paratroops? This is a ball game. The enemy’s on the ground. That throw was wide, Goldberg. Throw it like a sharpshooter. Give him the ball again. Throw it. Good. Like a sharpshooter. Very good. Keep the infield solid. No defensive holes in this war.”

We batted and threw the ball around, and it was warm and sunny, and there was the smooth, happy feeling of the summer soon to come, and the tight excitement of the ball game. We wanted very much to win, both for ourselves and, more especially, for Mr. Galanter, for we had all come to like his fist-thumping sincerity. To the rabbis who taught in the Jewish parochial schools, baseball was an evil waste of time, a spawn of the potentially assimilationist English portion of the yeshiva day. But to the students of most of the parochial schools, an inter-league baseball victory had come to take on only a shade less significance than a top grade in Talmud, for it was an unquestioned mark of one’s Americanism, and to be counted a loyal American had become increasingly important to us during these last years of the war.

So Mr. Galanter stood near home plate, shouting instructions and words of encouragement, and we batted and tossed the ball around. I walked off the field for a moment to set up my eyeglasses for the game. I wore shell-rimmed glasses, and before every game I would bend the earpieces in so the glasses would stay tight on my head and not slip down the bridge of my nose when I began to sweat. I always waited until just before a game to bend down the earpieces, because, bent, they would cut into the skin over my ears, and I did not want to feel the pain a moment longer than I had to. The tops of my ears would be sore for days after every game, but better that, I thought, than the need to keep pushing my glasses up the bridge of my nose or the possibility of having them fall off suddenly during an important play.”

Chaim Potok (17 februari 1929 – 23 juli 2002)

Cover

De Chinese schrijver Mo Yan werd geboren op 17 februari 1955 in Gaomi in de provincie Shandong. Zie ook alle tags voor Mo Yan op dit blog.

Uit: Red Sorghum (Vertaald door Howard Goldblatt)

“The ninth day of the eighth lunar month, 1939. My father, a bandit’s offspring who had passed his fifteenth birthday, was joining the forces of Commander Yu Zhan’ao, a man destined to become a legendary hero, to ambush a Japanese convoy on the Jiao-Ping highway. Grandma, a padded jacket over her shoulders, saw them to the edge of the village. “Stop here,” Commander Yu ordered her. She stopped.

“Douguan, mind your foster-dad,” she told my father. The sight of her large frame and the warm fragrance of her lined jacket chilled him. He shivered. His stomach growled.

Commander Yu patted him on the head and said, “Let’s go, foster-son.”

Heaven and earth were in turmoil, the view was blurred. By then the soldiers’ muffled footsteps had moved far down the road. Father could still hear them, but a curtain of blue mist obscured the men themselves. Gripping tightly to Commander Yu’s coat, he nearly flew down the path on churning legs. Grandma receded like a distant shore as the approaching sea of mist grew more tempestuous, holding on to Commander Yu was like clinging to the railing of a boat.

That was how Father rushed toward the uncarved granite marker that would rise above his grave in the bright-red sorghum fields of his hometown. A bare-assed little boy once led a white billy goat up to the weed-covered grave, and as it grazed in unhurried contentment, the boy pissed furiously on the grave and sang out: “The sorghum is red—the Japanese are coming—compatriots, get ready—fire your rifles and cannons—”

Someone said that the little goatherd was me, but I don’t know. I had learned to love Northeast Gaomi Township with all my heart, and to hate it with unbridled fury. I didn’t realize until I’d grown up that Northeast Gaomi Township is easily the most beautiful and most repulsive, most unusual and most common, most sacred and most corrupt, most heroic and most bastardly, hardest-drinking and hardest-loving place in the world. The people of my father’s generation who lived there ate sorghum out of preference, planting as much of it as they could. In late autumn, during the eighth lunar month, vast stretches of red sorghum shimmered like a sea of blood. Tall and dense, it reeked of glory; cold and graceful, it promised enchantment; passionate and loving, it was tumultuous.”

Mo Yan (Gaomi, 17 februari 1955)

Scene uit de gelijknamige film uit 1987

De Duitse schrijver Frederik Hetmann (eig. Hans-Christian Kirsch) werd geboren op 17 februari 1934 in Breslau. Zie ook alle tags voor Frederik Hetmann op dit blog.

Uit: Eine ziemlich haarige Geschichte

„Peter ist in einem Alter, in dem die Haare jedes Mal. wenn er beim Friseur gewesen ist, nicht kürzer, son-dern immer etwas länger geworden sind. Er nennt das, den Vater auf den Endzustand vorbereiten, ge-s wissermaßen Zentimeter für Zentimeter. Peters Vater kann sich nämlich über lange Haare unerhört aufregen. Er findet Haare, die fast bis auf die Schultern fallen, bei einem Jungen, wörtlich, kriminell. Bei Peter be-to decken die Haare mittlerweile schon fast die Ohren. Peters Vater ist bekannt, dass sich manche anderen Menschen langsam an langes Haar, selbst bei Jungen, gewöhnt haben, aber bei ihm ist das nicht zu erwarten. Er gehört andererseits aber nicht zu der Sorte von Vätern, die sagen: „So will ich’s. So wird’s ge-macht. Punktum, Schluss.” Er geht da etwas raffinierter vor. Peter nennt das Vor-gehen seines Vaters einfach Zermürbungstaktik. Dass er und sein Vater da die gleiche Taktik anwenden, diese Idee ist ihm aber noch nicht gekommen. Der Vater erwähnt Peters Haare mindestens zehnmal am Tag. Ach was, zehnmal reicht nicht hin, wenn man es genau zählt, jedenfalls nicht an Wochenenden. Der Vater sagt: „Also, Peter, ich kann mir nicht helfen, deine Haare sind entschieden zu lang für meinen Geschmack.” „Wie wäre denn die Länge nach deinem Geschmack”, erkundigt sich Peter spitz, „ich meine, genau … auf den Zentimeter?” Peters Vater stöhnt. Aber nach spätestens einer halben Stunde fällt schon wieder so eine Bemerkung. „Also, schau doch mal, das sieht ganz einfach ungepflegt aus”, sagt Peters Vater. „Was sollen denn die Leute von uns denken, wenn wir dich so rumlaufen lassen?”

Peter erinnert seinen Vater an Jesus Christus, an die Helden des Wilden Westens und an den Herrn auf dem Zehnmarkschein. „Und ich erinnere dich an Absalom. falls du weißt, wer das ist”, gibt der Vater zurück. „Mit dem nahm’s auch ein schlimmes Ende. Wie viel muss ich dir denn zum Taschengeld dazulegen, damit du dir das nächste Mal deine Haare auf eine vernünftige Länge kürzen lässt?” ;Typisch”, sagt Peter gereizt, „ihr denkt immer, alles ist käuflich.” „… war ja nur ein Vorschlag zur Güte, entschuldige bitte”, sagt der Vater penetrant behutsam.“

Frederik Hetmann (17 februari 1934 – 1 juni 2006)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 17e februari ook mijn vorige twee blogs van vandaag.

Zie voor bovenstaande schrijvers ook mijn blog van 17 februari 2007 en ook mijn blog van 17 februari 2008 en eveneens mijn blog van 17 februari 2009.