Dolce far niente

The Big River

The big river

rolls past our town

at Hobson’s Bend,

takes a slow look

at the houses on stilts

with timber creaking, paint flaking,

at the graveyard hushed

in the lonely shade,

at the fruit bats

dropping mango pulp

into the undergrowth,

at the foundry, and sawmill

grinding under a blazing sun,

at the pub with welcoming verandahs

shaded in wisteria vine,

at Durra Creek surrendering

to the incessant flow,

at Pearce Swamp upstream

on the creek among the willows

and rivergum,

at the storm clouds

rumbling over Rookwood Hill,

at the two boys

casting a line

on the crumbling bank,

at the cow fields

purple with Paterson’s curse,

at the jammed tree-trunks

washed down after summer thunder,

at the shop

with dead flies in the window display,

at the mosquito mangroves

and the sucking sound of mud crabs,

at the children throwing mulberries

the stain like lipstick.

The big river

rolls past our town,

takes a slow look,

and rolls away.

Brisbane

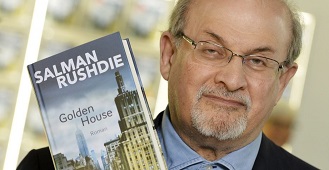

De Indisch-Britse schrijver en essayist Salman Rushdie werd geboren in Bombay op 19 juni 1947. Zie ook alle tags voor Salman Rushdie op dit blog.

Uit: The Golden House

“Sometimes, watching him, I thought of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, a simulacrum of the human that entirely failed to express any true humanity. His skin was brown leather and his smile glittered with golden fillings. His was a raucous and not entirely civil presence, but he was immensely rich and so, of course, he was accepted; but, in our downtown community of artists, musicians and writers, not, on the whole, popular.

We should have guessed that a man who took the name of the last of the Julio-Claudian monarchs of Rome and then installed himself in a domus aurea was publicly acknowledging his own madness, wrongdoing, megalomania, and forthcoming doom, and also laughing in the face of all that; that such a man was flinging down a glove at the feet of destiny and snapping his fingers under Death’s approaching nose, crying, “Yes! Compare me, if you will, to that monster who doused Christians in oil and set them alight to provide illumination in his garden at night! Who played the lyre while Rome burned (there actually weren’t any fiddles back then)! Yes: I christen myself Nero, of Caesar’s house, last of that bloody line, and make of it what you will. Me, I just like the name.” He was dangling his wickedness under our noses, reveling in it, challenging us to see it, contemptuous of our powers of comprehension, convinced of his ability easily to defeat anyone who rose against him.

He came to the city like one of those fallen European monarchs, heads of discontinued houses who still used as last names the grand honorifics, of-Greece or of-Yugoslavia or of-Italy, and who treated the mournful prefix, ex-, as if it didn’t exist. He wasn’t ex-anything, his manner said; he was majestic in all things, in his stiff-collared shirts, his cufflinks, his bespoke English shoes, his way of walking toward closed doors without slowing down, knowing they would open for him; also in his suspicious nature, owing to which he held daily separate meetings with his sons to ask them what their brothers were saying about him; and in his cars, his liking for gaming tables, his unreturnable Ping-Pong serve, his fondness for prostitutes, whiskey, and deviled eggs, and his often repeated dictum—one favored by absolute rulers from Caesar to Haile Selassie—that the only virtue worth caring about was loyalty. He changed his cellphone frequently, gave the number to almost no one, and didn’t answer it when it rang. He refused to allow journalists or photographers into his home but there were two men in his regular poker circle who were often there, silver-haired lotharios usually seen wearing tan leather jackets and brightly striped cravats, who were widely suspected of having murdered their rich wives, although in one case no charges had been made and in the other, they hadn’t stuck.”

Cover

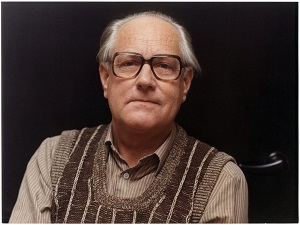

De Nederlandse dichter en schrijver Sybren Polet (pseudoniem van Sybe Minnema) werd geboren in Kampen op 19 juni 1924. Zie ook alle tags voor Sybren Polet op dit blog.

De geïmmigreerde schaduw

Dan, op een morgen

loopt geruisloos de rivier je kamer binnen,

je staat op,

je neemt plaats in een lichaam

als in een huis dat lang geleden verlaten is,

de ogen staan nog open, maar er groeien microscopisch kleine

bloemen in, enkele achtergebleven gedachten geuren

vaag nog, bijna komt er iets tot leven, er beweegt iets,

en je neemt plaats in een ander lichaam als een huis, bijna

zie je iets bewegen, iets glinstert, en je verandert van lichaam als van huis

en je ontmoet iemand die bewoonbaarder lijkt dan jij;

hij woont in hetzelfde huis,

verwarmt dezelfde droom,

ontdekt hetzelfde brood.

En zie, je pols is niet langer gekneusd, je bent genezen

als in een literatuur van ezelinnemelk, mijn dag knort tevreden

en zelfs je ouder worden is licht als moezelwijn.

Ik zie je slapen en komen, zoals een rivier slaapt en komt,

doornat van de zon, fietsend van de kou,

jij ziet mij slapen en komen: dronken struik, baldadige boom van het seizoen.

Tegen de morgen wordt het even donker:

het knipperen van een oog dat nauwelijks dicht,

liever dag is.

En naarmate de liefde helderder beelden aanneemt,

de wanden met kleur zoomt, de lampen van water aansteekt

en het beschikbare licht gelijkelijk over de dingen verdeelt, –

in die zin, misschien, wordt er iets geboren,

een droom van dezelfde vader,

een plant van dezelfde adem,

een jonge speelse marmot

die van ons drieën is.

De oude natuur – de nieuwe natuur

Let op: je ligt met je hand in de wond

van een wetenschappelijk landschap. Wie weet

ontdek je zo de vrolijke natuurwetenschap:

toekomend lichaam, karakter van cultuur, één-

cellig en ingeboren, ìk erfde het niet.

Opnieuw opgroeiend in bomen, boomwortels

als hagedissen, in eenvoudige betekenissen,

bedenken wij de tekens, de eerste: de boom

een boom, boomwortels als vingers, een bed van

harde vogels en zachte hagedissen.

Onder ons, boven ons is dezelfde zon.

De toekomst groeit als haren op ons hoofd.

De oude hemel van de schedel droomt eronder.

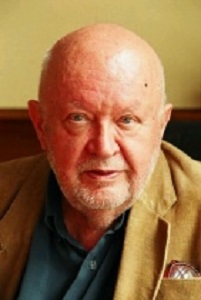

De Tsjechische schrijver Josef Nesvadba werd geboren op 19 juni 1926 in Praag. Zie ook alle tags voor Josef Nesvadba op dit blog.

Uit: The Half-wit of Xeenemuende (Vertaald door Iris Unwin)

“He

doesn’t let anybody else go in there,” his mother explained. “That’s

his kingdom,” and she winked conspiratorially at the teacher. “I’ve

watched him through the keyhole sometimes,” she went on as she conducted

the old man to the gate. “All day long he just plays about with a set

of boy’s tools and some stuff my husband brought home from the factory

for him. It’s just harmless play.”

“Are you so sure?” the man

replied as he looked across the road at the burned-out butcher’s shop.

“You never can tell with children like that. He’s not well, you know. He

really ought to be in an institution…”

That made Mrs. Habicht really angry; so he had gone over to the side of the neighbours who hated Bruno!

“Oh, no, not at all. I’m really quite fond of him. I’m sorry for him. But still, I think he’d be happier in a Home.”

“Never!” Mrs. Habicht stamped her foot with fury. “Never as long as I live!”

And

so the teacher decided to have a look a Bruno’s laboratory for himself

next day. He went straight round to the veranda at the back of the

house. The boy hadn’t locked himself in. He’d got a little kitten tied

up there and was torturing it with faradic current. The creature was

half-dead when the teacher rescued it. Bruno did not want to give it up

and they fought each other for it in silence, broken only by the boy’s

unintelligible grunts. The old man’s heart began to pain him. There was

only one thing to do. He aimed a blow at the boy’s head. Bruno dived

into a corner and stared at him with hatred.

“Krumme!” he

spluttered. “You Krumme!” Now Bruno’s governess had been Miss Krumme.

The tutor’s name was Brettschneider, and the boy knew that very well.

The old man felt a strange horror creeping over him. He did not even

begin lessons that day. Avoiding Mrs. Habicht, he went to see her

husband at the works.

He was led along endless underground passages,

with two armed men preceding him and two behind. It was like being in

an anthill that was larger than life. The engineer listened to him

impatiently.

“I know the boy has been responsible for a lot of

trouble. He’s a mischievous lad. But I really can’t imagine how he could

have had anything to do with either of the tragedies.”

“Well, we’ll

see,” said the teacher. “Nothing is going to make me sleep at home

tonight. You can keep watch with me in the garden if you like.” He lived

in a little house near the station.

“You must excuse me. I’ve other things to think about. More important things…” Mr. Habicht refused the suggestion.”

Praag

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata:

De Nederlandse schrijfster Elke Geurts werd geboren in Heijen in 1973. Zie ook alle tags voor Elke Geurts op dit blog.

Uit: Ik nog wel van jou

“Vanaf daar, leunend tegen het aanrechtblad, zag ik de vele omhelzingen die zich in dit halletje hadden afgespeeld aan mij voorbijtrekken.

Vanaf hier zie ik ook hoe ik een paar maanden daarna, in een geknakte houding, onder de kapstok zal liggen, en het er niet alleen maar uitziet alsof ik boven op de schoenen en de lege flessen in de hoek ben gesmeten, maar dat het ook daadwerkelijk zo is.

Man heeft mij van zich afgeworpen. Mijn achterhoofd tegen het kinderkapstokje aan de muur. Mijn wang is rood, mijn slaap bonkt, ik voel de zwelling. Ik huil als een klein kind. ‘Jij wil mij gewoon wegdoen. Mij?’

Het leven is echt een slechte film. Alleen al daarom is het zaak dat wij mensen er iets beters van maken.

Dit is een slecht verhaal, en als ik niet zou proberen de loop ervan te veranderen, er een goed verhaal van te maken of ten minste iets beters, ben ik als schrijver geen knip voor de neus waard. Dat is mijn enige taak.

Ik zie hoe ik zijn borstkas met één hand tegen de voordeur zal drukken, mijn knie in zijn ballen stoot, en zijn hoofd, het hoofd dat ik zo lang heb geliefkoosd, wordt helemaal scheefgetrokken, want met die andere hand trek ik zo hard ik kan aan zijn krullen. Hij zal brullen: ‘Kutwijf, jij hebt mijn leven verpest.’ En: ‘Rot op. Ik smijt je het huis uit.’

‘Dat is wat je eigenlijk wilt, hè?’ schreeuw ik. ‘Dat is wat je echt wilt.’

Daarom moeten die haren allemaal tegelijk uit zijn hoofd. Hij kermt. Zo kom ik dus uiteindelijk onder die kapstok terecht.”

De Tsjechische schrijver Marek Šindelka werd geboren in 1984 in Polička. Šindelka studeerde naast zijn literaire activiteiten cultuurwetenschappen aan de Karelsuniversiteit, alsmede scenarioschrijven aan de FAMU in Praag. Voor zijn debuut, de dichtbundel “Strychnin a jiné básně” (Strychnine en andere gedichten), ontving hij in 2006 de Jiří-Orten-prijs. In 2008 publiceerde Šindelka zijn eerste roman “Chyba” (De fout), die in 2011 ook als strip verscheen. Daarnaast schreef Šindelka artikelen voor de Tsjechische literaire tijdschriften Souvislosti, A2 en Host, evenals de verhalenbundels “Zůstaňte s námi” (Blijf bij ons), waarvoor hij de 2012 Magnesia Litera Prijs ontving in de categorie proza, en “Mapa Anny” (Anna in kaart gebracht). In 2016 verscheen de tweede roman “Únava materiálu” (Materiaalmoeheid). In 2017 ontving Šindelka opnieuw de Magnesia Litera-prijs voor proza voor deze roman.

Uit: Materiaalmoeheid (Vertaald door Edgar de Bruin)

“Een rugzak plofte in de sneeuw, gevolgd door een jongen. Avond. Gloed aan de einder. Een rauw stuk hemel uitgesneden in het grijs. De adem zichtbaar. Het ijzeren hek fonkelend van de ijzel. Ook de betonmuur fonkelde. Achter de muur een rij ruiten, verlichte vensters, een stralende flat. De jongen kwam vlug overeind, klopte de sneeuw van zijn knieën.

Over een winding van het prikkeldraad hing een deken met een inventarisnummer. Alles heeft een nummer hier, flitste het door zijn hoofd. Hij keek even om zich heen, deed de rugzak om. Er zat een shirtje in, zeep, lucifers, een mes dat hij uit de kantine had gepikt. In zijn zak een zorgvuldig opgevouwen briefje met daarop de naam van een stad in het noorden. Hij moet naar het noorden. Daar ergens zit zijn broer. Maar voor alles moet hij aan een telefoon zien te komen, of ten minste een kaart. Nee. Eerst moet hij de deken van het hek trekken en meenemen, anders snappen ze hem. Hij had hem ook tegen de vrieskou nodig. Zo’n winter heeft hij nog nooit meegemaakt. Hij heeft de deken nodig om niet dood te vriezen.

Hij sjorde aan de deken, maar de prikkeldraadpunten sneden alleen maar steeds dieper in de vezels.

Het had geen zin. In de verte hoorde hij een hond kort blaffen. Even werd het zwart voor zijn ogen. Hij liet de deken zitten. Zette het op een rennen. Verdween tussen de bomen. Verwondde zijn handen.

Hij had zijn huid aan iets opengehaald. Wreef zijn handpalm schoon met sneeuw. Zoog de wond uit.

Het bloed klopte voelbaar binnen in zijn palm. Zijn ze er al achter gekomen? De deken hing aan het hek, hij keek nog een keer om, maar er was geen tijd. Hij bleef maar rennen. Takken zwiepten langs zijn hoofd, kronkelende barsten van struiken tegen de hemel, boomtakken dor van de vorst. Hij had ze kunnen afbreken.

Het liefst had hij ze allemaal afgebroken, had hij tijd gehad. Hij stampte door de sneeuw. Gleed uit, maar sprong meteen weer overeind, gaf een trap tegen de eerste de beste boomstam en rennen maar weer. Hij haatte die bomen, maandenlang had hij er door de getraliede ramen van dat gebouw op uitgekeken, kon hij volgen hoe ze hun bladeren verloren, hoe ze hun sapstroom onder de grond terugtrokken,hoe ze breekbaar werden.”

Zie voor de schrijvers van de 19e juni ook mijn blog van 19 juni 2018.