Dolce far niente

Nuit d’été

Le violon, d’un chant très profond de tristesse,

Remplit la douce nuit, se mêle aux sons des cors,

Les sylphes vont pleurant comme une âme en détresse,

Et les coeurs des arbres ont des plaintes de morts.

Le souffle du Veillant anime chaque feuille ;

Aux amers souvenirs les bois ouvrent leur sein ;

Les oiseaux sont rêveurs ; et sous l’oeil opalin

De la lune d’été ma Douleur se recueille…

Lentement, au concert que font sous la ramure

Les lutins endiablés comme ce Faust ancien,

Le luth dans tout mon coeur éveille en parnassien

La grande majesté de la nuit qui murmure

Dans les cieux alanguis un ramage lointain,

Prolongé jusqu’à l’aube, et mourant au Matin.

Montreal, de geboorteplaats van Emile Nelligan

De Franse schrijver Florian Zeller werd op 28 juni 1979 in Parijs geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Florian Zeller op dit blog.

Uit: The Father (Vertaald door Christopher Hampton)

“ANNE. Where? Where did you leave it?

ANDRÉ. Mm? Somewhere. Can’t remember. All I know is it’s now nowhere to be found. Nowhere to be found. I can’t find it, there’s your proof. That girl stole it from me. I know it. So yes, maybe I called her a… Like you say. It’s possible. Maybe I got a bit annoyed. All right. If you like. But, really, Anne, a curtain rod, come on…raving mad, I’m telling you.

Anne sits down. She looks winded.

What’s the matter?

ANNE. I don’t know what to do.

ANDRÉ. About what?

ANNE. We have to talk, Dad.

ANDRÉ. That’s what we’re doing, isn’t it?

ANNE. I mean, seriously.Pause.This is the third one you’ve…

ANDRÉ. I said, I don’t need her! I don’t need her or anyone else! I can manage very well on my own!

ANNE. She wasn’t easy to find, you know. It’s not that easy. I thought she was really good. A lot of good qualities. She… And now she doesn’t want to work here anymore.

ANDRÉ. You’re not listening to what I’m telling you. That girl stole my watch! My watch, Anne! I’ve had that watch for years. For ever! It’s of sentimental value. It’s… I’m not going to live with a thief.

ANNE. (Exhaustedly.) Have you looked in the kitchen cupboard?

ANDRÉ. What?

ANNE. In the kitchen cupboard. Behind the microwave. Where you hide your valuables.

Pause.

ANDRÉ. (Horrified.) How do you know?

ANNE. What?

ANDRÉ. How do you know?

ANNE. I just know, that’s all. Have you looked there for your watch?”

Poster voor een voorstelling in Londen, 2018

De Britse dichteres en schrijfster Sophie Hannah werd geboren in Manchester op 28 juni 1971. Zie ook alle tags voor Sophie Hannah op dit blog.

Your Dad Dit What?

Where they have been, if they have been away,

or what they’ve done at home, if they have not –

you make them write about the holiday.

One writes My Dad did. What? Your Dad did what?

That’s not a sentence. Never mind the bell.

We stay behind until the work is done.

You count their words (you who can count and spell);

all the assignments are complete bar one

and though this boy seems bright, that one is his.

He says he’s finished, doesn’t want to add

anything, hands it in just as it is.

No change. My Dad did. What? What did his Dad?

You find the ‘E’ you gave him as you sort

through reams of what this girl did, what that lad did,

and read the line again, just one ‘e’ short:

This holiday was horrible. My Dad did.

Occupational Hazard

He has slept with accountants and brokers,

With a cowgirl (well, someone from Healds).

He has slept with non-smokers and smokers

In commercial and cultural fields.

He has slept with book-keepers, book-binders,

Slept with auditors, florists, PAs

Child psychologists, even child minders,

With directors of firms and of plays.

He has slept with the stupid and clever.

He has slept with the rich and the poor

But he sadly admits that he’s never

Slept with a poet before.

Real poets are rare, he confesses,

While it’s easy to find a cashier.

So I give him some poets’ addresses

And consider a change of career.

De Poolse dichter, vertaler en uitgever Ryszard Krynicki werd geboren op 28 juni 1943 in St.Valentin, Lager Wimberg, Oostenrijk. Zie ook alle tags voor Ryszard Krynicki op dit blog.

Now That I know

Now that I know you didn’t die:

the grind of a braking tram, the telegram,

a sharply shattered glance, the dream about a bloodless child,

the weather forecast and—whatever happened

now that I know it’s not about you,

they speak of someone else to others, strangers, kin,

in graying voices

they become mirrors

My beloved

My beloved, moments ago

you still walked in your favorite black dress

beneath a sun projecting

shadows of shifting triangles

(legible even to me, who

never understood geometry):

the distance grows, draws close,

a relentless straight line

penetrates my heart,

between us lies not even the smoke

of a train departing years ago

but this intimate remoteness

in labyrinths of seals, stamps,

coiled wire and borders

weaves its barbed net

Vertaald door Clare Cavanagh

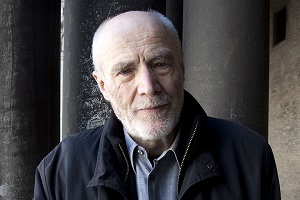

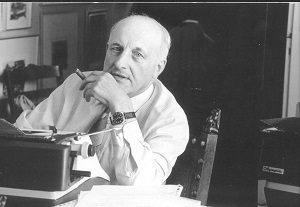

De Amerikaanse schrijver en journalist Mark Helprin werd geboren in New York op 28 juni 1947. Zie ook alle tags voor Mark Helprin op dit blog.

Uit: The Pacific and Other Stories

“To the question what is the difference between Venice and Milan other than a difference in tone, in the sunlight, and in the air, the answer is that Milan is where you busy yourself with the world as if what you did really mattered, and there time seems not to exist. But in Venice time seems to stop, you are busy only if you are a fool, and you see the truth of your life. And, whereas in Milan beauty is overcome by futility, in Venice futility is overcome by beauty.

It isn’t because of the architecture or the art, the things that people go to look at and strain to preserve. The quality of Venice that accomplishes what religion so often cannot is that Venice has made peace with the waters. It is not merely pleasant that the sea flows through, grasping the city like the tendrils of a vine, and, depending upon the light, making alleys and avenues of emerald or sapphire, it is a brave acceptance of dissolution and an unflinching settlement with death. Though in Venice you may sit in courtyards of stone, and your heels may click up marble stairs, you cannot move without riding upon or crossing the waters that someday will carry you in dissolution to the sea. To have made peace with their presence is the great achievement of Venice, and not what tourists come to see.

What Rosanna can do with her voice — the sublime elevation that is the province of artists, anyone can do in Venice if he knows what to look for and what to ignore. Should you concentrate there on the exquisite, or should you study too closely the monuments and museums, you will miss it, for it comes gently and without effort, and moves as slowly as the tide.

Despite the fact that you are more likely to feel this quality if you are not distracted by luxury, I registered at the Celestia. The streets near San Marco are far too crowded and not as interesting as those quieter areas on other islands and in other districts, and they have a deficit of greenery and sunlight. And the Celestia, with its 2,600-count linen and stage-lit suites, is the kind of luxury that removes one from the spirit of life, but I went there anyway almost as a way of spiting Rosanna, who was paying for it, and because that is where we always stayed in Venice, and I wanted to accumulate more hotel-stay points. In that I am compulsive. Once I start laying-in a store of a certain commodity, like money, I get very enthusiastic about building it up.”

De Oostenrijkse schrijfster Marlene Streeruwitz werd geboren op 28 juni 1950 in Baden bij Wenen. Zie ook alle tags voor Marlene Streeruwitz op dit blog.

Uit: Das wird mir alles nicht passieren…

„Es war nicht wegen des Sex.

Sie macht ihm keinen Vorwurf wegen des Sex. Aber es war alles schwierig geworden, und die Probleme schleppten sich so unlösbar weiter, weil sie im Bett nicht mehr zueinander fanden und danach dann wieder miteinander lachen hätten können. (Andrea S., Seite 5)

Er war noch zu jung. Er sollte sich nicht Gedanken machen. Er musste sich nicht entscheiden. Die Eydergün hätte den Vorteil gehabt, dass sie mit seinen Eltern reden hätte können. Seine Mutter hätte sich über eine Frau wie die Eydergün gefreut. Deswegen. Seine Mutter trug das Kopftuch nicht so. Seine Mutter trug immer ein Kopftuch. Aber sie verbarg ihre Haare nicht ganz. Sie trug kein Untertuch. Die Eydergün. Man konnte kein Haar von ihr sehen. Er musste seine Mutter fragen. Mit der Frau von Ömar waren seine Eltern freundlich. Sie waren zur Hochzeit gegangen und seine Mutter hatte geweint und ihnen Glück gewünscht. Von der Sandra wusste er jede neue Farbschattierung. Die Sandra färbte ihre Haare alle Augenblicke anders und hatte ihre Haare damit kaputtgemacht. Aber die Punkfrisur schaute gut aus. Im Kurs wurde das besprochen. Dass er sich für die Sandra interessierte, aber dass er der Eydergün beim Lernen half.

Die alte Frau hatte mit dem Kopieren aufgehört. Sie kam zur Kassa und fragte, ob er ihr einen Locher borgen könnte. Er stand auf und nahm den Locher. Sie gingen nebeneinander zum Kopiergerät. Da sei sie sehr froh, das er einen Locher herborgen könne. Dann könne sie nämlich dieses Blatt einordnen. Er reichte ihr den Locher. Sie habe in diesem Ordner jetzt schon einen großen Teil ihrer Bücher eingefangen, sagte die alte Frau. Sie lochte ein Blatt, auf dem die Buchrücken klar zu sehen waren. Sie kopiere die Buchrücken und habe sich diesen Ordner gemacht, weil sie aus ihrer Wohnung müsse und dann kein Platz mehr sein würde. Für die Bücher würde dann kein Platz mehr sein. Und dann habe sie die Ordner. Als stünden sie noch im Regal. Die alte Frau reichte ihm den Locher und er nahm ihn zurück.

Die alte Frau steckte vorsichtig den Ordner in ihren Rucksack Dann begann sie die Bücher einzuordnen.“

De Nederlandse dichteres en schrijfster Fritzi Harmsen van Beek werd geboren in Blaricum op 28 juni 1927. Zie ook alle tags voor Fritzi Harmsen van Beek op dit blog

Moeder of vader,

niemand, ook hij niet, bleek van meerdere zeeën

overspoeld, verwekt uit menigvuldig zaad. Toch

wilde hij een zwaar, machtig man zijn, het bed

delen met deze ene onwijze kat, gediend zijn van

haar haakse pootjes, aangeblikt door haar reliëf-

loos oog en haastig, gruwelijk besnord, wilde hij

nestelen in al haar takken bloot. (Des nachts,

leesgierig opgesloten met Mark Twain in het

closet, hoorden wij, wel beangst maar schaamteloos,

gewetenloos van onschuld hun verlate gang naar

het nabije, snorkende bidet.) Hij wou haar koorts,

haar ogen sluit en tong klem. Hij wou haar wel van

wanhoop schubbig, vel gestold en vederloos volslagen,

geplunderd als een engel, die uitzinniger bemind,

van weerzin eindelijk bezweek en roerloos werd. Hij

werd bij haar crematie vreemd. Wij stonden machteloos,

hun misselijk nageslacht, de zwakke, hoewel kritisch

hoogst begaafde materialisatie van hun fictie, tot

zijn dood, tijdens het zenuwachtig zoeken naar een

voorwerp dat hij in zijn zak droeg, ons tenslotte heeft

ontzet. Nu zijn wij dikwijls droevig en besluiteloos,

aan niemand dan onszelve meer verwant. Wij zoeken nu

geen schuilhoek meer voor overwintering. Wij zeggen nog

wel, weet je wat, laten we veel geld gaan verdienen,

maar ’s avonds laat dronken, in omhelzingen verslonden,

spreken wij, ten minste triomfantelijk, het laatste

woord: Nu kust hem niemand, niemand meer, de arme oude man

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 28e juni ook mijn blog van 28 juni 2018 en ook mijn blog van 28 juni 2014 deel 2.