Dolce far niente

Midsummer in the Catskills

The strident hum of sickle-bar,

Like giant insect heard afar,

Is on the air again;

I see the mower where he rides

Above the level grassy tides

That flood the meadow plain.

The barns are fragrant with new hay,

Through open doors the swallows play

On wayward, glancing wing;

The bobolinks are on the oats,

And gorging stills the jocund throats

That made the meadows ring.

The cradlers twain, with right good-will,

Leave golden lines across the hill

Beneath the midday sun.

The cattle dream ‘neath leafy tent,

Or chew the cud of sweet content

Knee-deep in pond or run.

July is on her burning throne,

And binds the land with torrid zone,

That hastes the ripening grain;

While sleepers swelter in the night,

The lusty corn is gaining might

And darkening on the plain.

The butterflies sip nectar sweet

Where gummy milkweeds offer treat

Or catnip bids them stay.

On banded wing grasshoppers poise,

With hovering flight and shuffling noise,

Above the dusty way.

The thistle-bird, midsummer’s pet,

In billowy flight on wings of jet,

Is circling near his mate.

The silent waxwing’s pointed crest

Is seen above her orchard nest,

Where cherries linger late.

The dome of day o’erbrims with sound

From humming wings on errands bound

Above the sleeping fields;

The linden’s bloom faint scents the breeze,

And, sole and blessed ‘mid forest trees,

A honeyed harvest yields.

Poisèd and full is summer’s tide,

Brimming all the horizon wide,

In varied verdure dressed;

Its viewless currents surge and beat

In airy billows at my feet

Here on the mountain’s crest.

Through pearly depths I see the farms,

Where sweating forms and bronzèd arms

Reap in the land’s increase;

In ripe repose the forests stand,

And veilèd heights on every hand

Swim in a sea of peace.

Kirkside Park in Roxbury, New York, de geboorteplaats van John Burroughs

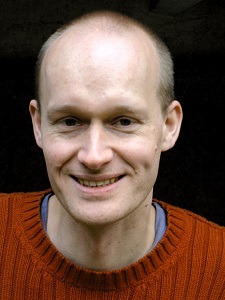

De Oostenrijkse schrijver Arno Geiger werd geboren op 22 juli 1968 in Bregenz, Vorarlberg. Zie ook alle tags voor Arno Geiger op dit blog.

Uit: Unter der Drachenwand

“Im Himmel, ganz oben im Himmel, ganz oben, konnte ich einige ziehende Wolken erkennen, und da begriff ich, ich hatte überlebt. / Später stellte ich fest, dass ich doppelt sah. Alle Knochen taten mir weh. Am nächsten Tag Rippfellreizung, zum Glück gut überstanden. Doch auf dem rechten Auge sah ich weiterhin doppelt, und der Geruchssinn war weg.So hatte mich der Krieg auch diesmal nur zur Seite geschleudert. im ersten Moment war mir gewesen, als würde ich von dem Krachen verschluckt und von der ohnehin alles verschluckenden Steppe und den ohnehin alles verschluckenden Flüssen, an diesem groben Knie des Dnjepr. Unter meinem rechten Schlüsselbein lief das Blut in leuchtenden Bächen heraus, ich schaute hin, das Herz ist eine leistungsfähige Pumpe, und es wälzte mein Blut jetzt nicht mehr in meinem Körper im Kreis, sondern pumpte es aus mir heraus, bum, bum. In Todesangst rannte ich zum Sanitätsoffizier, der die Wunde tamponierte und mich notdürftig verband. Ich schaute zu, in staunendem Glück, dass ich noch atmete. / ein Granatsplitter hatte die rechte Wange verletzt, äußerlich wenig zu sehen, ein weiterer Splitter steckte im rechten Oberschenkel, schmerzhaft, und ein dritter Splitter hatte unter dem Schlüsselbein ein größeres Gefäß verletzt, Hemd, Rock und Hose waren blutgetränkt. Das unbeschreibliche, mit nichts zu vergleichende Gefühl, das man empfindet, wenn man überlebt hat. Als Kind der Gedanke: Wenn ich groß bin. Heute der Gedanke: Wenn ich es überlebe. / Was kann es Besseres geben, als am Leben zu bleiben? Es passierte in genau derselben Gegend, in der wir um die gleiche Zeit vor zwei Jahren gestanden waren. Alles hatte ich gut in erinnerung, ich erkannte die Gegend sofort wieder, die Wege, alles immer noch dasselbe. Aber besser waren die Wege seither nicht geworden. Wir lagen neben einem zerstörten Dorf, die meiste Zeit unter Beschuss. in der Nacht war es schon so kalt, dass uns das Wasser im Kübel gefror. Auch auf den Zelten lagen Eiskrusten. / Unser Rückzugsmarsch war ein einziger Feuerstreifen, schauerlich anzusehen. Und ernüchternd, sich darüber Gedanken zu machen. Alle Strohschober brannten, alle Kolchosen brannten, gerade die Häuser blieben meistenteils stehen. Die Bevölkerung sollte nach rückwärts evakuiert werden, doch ließ sich das nur teilweise durchführen, zum Großteil waren die Leute nicht wegzubringen, es war ihnen egal, ob man sie erschoss, aber weg wollten sie auf gar keinen Fall. Und der Krieg arbeitete sich weiter, für die einen nach vorn, für die andern nach hinten, aber immer in der blutigsten, unverständlichsten Raserei.“

Cover

De Vlaamse dichter Roland Jooris werd geboren in Wetteren op 22 juli 1936. Zie ook alle tags voor Roland Joris op dit blog.

Achtergrond

Afgewend

met zijn rug naar

het zijnde spaart hij

zijn stilstand in verstomming

uit

de avond tegemoet

de helderheid achter donkere

glazen, de opgooi van stemmen

binnen het afgelijnde, het doffe

leder dat men in het wilde

trapt

doelloos

staart de mens naar

wat hem invalt als een schaduw

in de war van zijn

bestaan

Eensklaps

Als een duif opvliegt

neemt geen geluid

haar plaats

nog in;

Eensklaps

en wit

laat zij slechts

verte

in mij na.

Minimal

Vogel wipt.

Tak kraakt.

Lucht betrekt.

Bijna niets

om naar te kijken

en juist dat

bekijk ik.

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Susan Eloise Hinton werd geboren op 22 juli 1948 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Zie ook alle tags voor Susan Hinton op diit blog.

Uit: Rumble Fish

“We

went home. The Motorcycle Boy sat on the mattress and read a book. I

sat next to him and smoked one cigarette after another. He sat there

reading and I sat there waiting. I didn’t know what I was waiting for.

About three years before, a doped-up member of the Tiber Street Tigers

had wandered over onto Packer territory and got beat up and crawled

back. I remember waiting around in a funny state of tenseness, like

seeing lightning and waiting for thunder. That was the night of the last

rumble, when Bill Braden died from a bashed-in head. I’d been sliced up

real bad by a Tiger with a kitchen knife, and the Motorcycle Boy had

sent at least three guys to the hospital, laughing out loud right in the

middle of the whole mess of screaming, swearing, grunting, fighting

people. I’d forgotten about that. Sitting there reminded me. It was much

harder to wait than to fight. “Both home again?” The old man came in

the door. He liked to stop in and change his shirt before he went out to

the bars for the night. It didn’t matter that the one he changed into

was usually as dirty as the one he took off. It was just something he

liked to do. “I want to ask you somethin’,” I said. “Yes?” “Was—is—our

mother nuts?”

“Your

mother,” he said distinctly, “is not crazy. Neither, contrary to

popular belief, is your brother. He is merely miscast in a play. He

would have made a perfect knight, in a different century, or a very good

pagan prince in a time of heroes. He was born in the wrong era, on the

wrong side of the river, with the ability to do anything and finding

nothing he wants to do.” I looked at the Motorcycle Boy to see what he

thought. He hadn’t heard a word of it. And even though I didn’t have

much hope that the old man could tell me something in plain English, I

had to ask him something else. “I think that I’m gonna look just like

him when I get older. Whadd’ya think?” My father looked at me for a long

moment, longer than he’d ever looked at me. But still, it was like he

was seeing somebody else’s kid, not seeing anybody that had anything to

do with him. “You better pray to God not.” His voice was full of pity.

“You poor child,” he said. “You poor baby.”

The

Motorcycle Boy broke into the pet store that night. I was with him. He

didn’t ask me along. I just went. “Look, you need some money? I’ll get

you some money,” I said desperately. I knew he didn’t need any money. I

just couldn’t think of any other reason for what he was doing.

“Anyway…” I kept on talking, saying anything so I couldn’t feel the

deadly silence,”…if you want money, liquor stores are the best bet.”

Scene uit de gelijknamige film uit 1983 met Dennis Hopper (Father) en Matt Dillon (Rusty James)

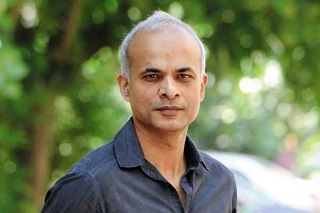

De Indiase schrijver en journalsit Manu Joseph werd geboren op 22 juli 1974 geboren in Kottayam en groeide op in Chennai. Zie ook alle tags voor Manu Joseph op dit blog.

Uit: The Illicit Happiness of Other People

“Ousep

Chacko, according to Mariamma Chacko, is the kind of man who has to be

killed at the end of a story. But he knows that she is not very sure

about this sometimes, especially in the mornings. He sits at his desk,

as usual, studying a large pile of cartoons, trying to solve the only

mystery that matters to her. He does not ask for coffee, but she brings

it anyway, landing the glass on the wooden desk with minor violence to

remind him of last night’s disgrace. She flings open the windows,

empties his ashtray and arranges the newspapers on the table. And when

he finally leaves for work without a word, she strands in the hall and

watches him go down the stairs.

On

the playground below, a hard brown earth with stray grass, Ousep walks

with quick short strides towards the gate. He can see the other men, the

good husbands and the good fathers, their black shoes polished, serious

shirts already damp in the humid air. They walk to the scooter shed,

carrying inverted helmets that contain their outrageously small

vegetarian lunches. More men emerge from the stair way tunnels of Block

A, which is an austere white building with three floors. Their tidy,

auspicious wives in cotton saris now appear in the balconies to bid

goodbye. They are mumbling prayers, smiling at other women, peeping with

one eye into their own blouses.

The

men never greet Ousep. They turn away, or become interested in the

ground, or wipe their spectacles. But among their own, they have great

affection. They are a fellowship, and they can communicate by just

clearing the phlegm in their throats.

“Gorbachev,” a delicate man says.

“Gorbachev,” the other one says.

Having

thus completed the analysis of the main story in The Hindu, which is

Mikhail Gorbachev’s election as the first executive president of the

Soviet Union, they walk towards their scooters. A scooter in Madras is a

man’s promise that he will not return home drunk in the evening.

Hard-news reporters like Ousep Chacko consider it an insult to be seen

on one, but these men are mostly bank clerks. They now hold the

handlebars of their scooters and stand in a languid way. Then they kick

suddenly as if to startle the engine into life.

At

the gates, the fragile watchman stands in a farcical para-military

outfit that puffs in the wind, and he cautiously salutes his foe. Ousep

nods without looking. That always gets the guard’s respect. Ousep turns

for a glimpse of the women on the balconies, and they pretend they were

not looking at him. On his own balcony on the third floor there is no

one.”

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver Stephen Vincent Benét werd geboren op 22 juli 1898 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Zie ook alle tags voorStephen Vincent Benét op dit blog.

Ghosts Of A Lunatic Asylum

Here, where men’s eyes were empty and as bright

As the blank windows set in glaring brick,

When the wind strengthens from the sea — and night

Drops like a fog and makes the breath come thick;

By the deserted paths, the vacant halls,

One may see figures, twisted shades and lean,

Like the mad shapes that crawl an Indian screen,

Or paunchy smears you find on prison walls.

Turn the knob gently! There’s the Thumbless Man,

Still weaving glass and silk into a dream,

Although the wall shows through him — and the Khan

Journeys Cathay beside a paper stream.

A Rabbit Woman chitters by the door —

— Chilly the grave-smell comes from the turned sod —

Come — lift the curtain — and be cold before

The silence of the eight men who were God!

Love In Twilight

There is darkness behind the light — and the pale light drips

Cold on vague shapes and figures, that, half-seen loom

Like the carven prows of proud, far-triumphing ships —

And the firelight wavers and changes about the room,

As the three logs crackle and burn with a small still sound;

Half-blotting with dark the deeper dark of her hair,

Where she lies, head pillowed on arm, and one hand curved round

To shield the white face and neck from the faint thin glare.

Gently she breathes — and the long limbs lie at ease,

And the rise and fall of the young, slim, virginal breast

Is as certain-sweet as the march of slow wind through trees,

Or the great soft passage of clouds in a sky at rest.

I kneel, and our arms enlace, and we kiss long, long.

I am drowned in her as in sleep. There is no more pain.

Only the rustle of flames like a broken song

That rings half-heard through the dusty halls of the brain.

One shaking and fragile moment of ecstasy,

While the grey gloom flutters and beats like an owl above.

And I would not move or speak for the sea or the sky

Or the flame-bright wings of the miraculous Dove!

Cover biografie

De Amerikaanse schrijver Tom Robbins werd geboren op 22 juli 1936 in Blowing Rock, North Carolina. Zie ook alle tags voor Tom Robbins op dit blog.

Uit: Wild Ducks Flying Backward

“Physically,

my pilgrimage commenced in downtown Seattle. Downtown Seattle has long

been my “stomping grounds,” as they say, although in the past couple of

years it’s lost its homey air. A side effect of Reaganomics was

skyscraper fever. Developers, taking advantage of lucrative tax breaks,

voodoo-pinned our city centers with largely unneeded office towers. In

downtown Seattle, for some reason, most of the excess buildings are

beige. Seattleites complain of beige a vu: the sensation that they’ve

seen that color before.

In

any case, it was in a Seattle parking lot, flanked by beige edifices,

that I exchanged cars with my chiropractor. He took my customized Camaro

Z-28 convertible, a quick machine whose splendid virtues do not include

comfort on long-distance hauls; I took his big, new Mercedes.

If,

indeed, the reader should decide to motor to Nevada and it proves to

exceed an afternoon’s j aunt, may I suggest swapping cars with a

chiropractor? Chiropractors’ cars are not like yours or mine. Theirs

tend to be massage parlors on wheels, equipped with the latest

breakthroughs in therapeutic seating, lumbar cushions, and

vertebrae-aligning headrests. It’s like rolling along in a technological

spa. The driver can get a spinal adjustment and a speeding ticket

simultaneously.

So

relaxed was I in that tea-green Mercedes that I didn’t look around when

I heard my chiropractor burn a quarter inch of rubber off the Camaro’s

tires. In a certain way, it was reminiscent of the movie Trading Places.

As the good doctor tore off to drag sorority row at the University of

Washington, I oozed through the beige maze with a serene, chiropractic

smile, braking tenderly in front of Alexa’s apartment, and then in front

of Jon’s.

For

days to come, the three of us, Alexa, Jon, and your pilgrim, would take

turns piloting the doctor’s clinical dreamboat along tilting tables of

rural landscape. Once we’d crossed the tamed Columbia and were

traversing the vastness of eastern Oregon, once we were out of the wet

zone and into the dry zone, out of the vegetable zone and into the meat

zone, out of the fiberglass-shower-stall zone and into the

metal-shower-stall zone, we would glide through a seemingly endless

variety of ecosystems, most of them virtually relieved of the more

obvious signs of human folly, all of them unavoidably gorgeous.”

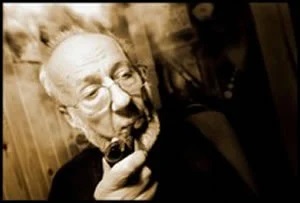

De Duitse schrijver Oskar Maria Graf werd geboren op 22 juli 1894 in Berg am Starnberger See. Zie ook alle tags voor Oskar Maria Graf op dit blog.

Uit: Das Leben meiner Mutter

„Allem Anschein nach aber ist er verschont geblieben, denn Colonus berichtet nichts Gegenteiliges, ja, er erwähnt die Heimraths nicht einmal mit einem einzigen Wort. Wenngleich dies nun durch nichts belegt werden kann, bei einiger Verwegenheit der Vorstellung könnte man fast annehmen, der Aufhauser Bauer habe zur Rettung seines Hab und Gutes einen anderen Weg als die kopflose Flucht in die Wälder eingeschlagen. Vielleicht sagte er sich in stumpfer Gelassenheit: »Krieg ist eben Krieg, und alles hängt vom Zufall ab. Was hab’ ich schon davon, wenn ich davonlaufe und beim Zurückkommen statt meines schönen Hofes einen Aschenhaufen finde! Lieber gleich als Heimrathbauer sterben, bevor ich ein Leben lang als Bettler im ungewissen herumlaufe. Bleiben wir und schauen wir, was wird! Besser ist’s, einiges einzubüßen, als alles sinnlos zugrunde gehen zu lassen.« Vielleicht ließ er Tür und Tor offen und empfing die rauhen Kriegsleute unerschrocken wie ein biederer Wirt, bot ihnen bereitwillig Speis und Trank an und ließ sie kaltblütig gewähren. Eine so abgebrühte, breit lachende, bezwingend-schlaue Bauernfreundlichkeit, die ein Heimrath dem anderen von Generation zu Generation vererbte, mag vielleicht auf die hitzigen Schweden derart verblüffend gewirkt haben, daß sie nach all dem wilden Fliehen und hilflos bittenden Jammern, das ihnen bis jetzt überall begegnet war, eine solche Einkehr als angenehme Abwechslung empfanden und schließlich abzogen. Demütig und gar nicht eitel darüber, daß sein kluger Einfall sie vor dem Schlimmsten bewahrt hatte, aber doch tief zufrieden, wird der Heimrath mit den Seinen dem Allmächtigen gedankt haben. Denn nichts vermochte der Mensch, alles stand in »Gottes Hand«. Gewiß sind das nur Mutmaßungen, dennoch ist eine so kühne Schlußfolgerung, wenn man alles scharf überdenkt, nicht ganz von der Hand zu weisen. In den darauffolgenden zwei Jahren raffte die Pest, die mit dem unseligen Krieg in die Gaue gekommen war, zahlreiche Familien dahin. Das pfarramtliche Totenregister enthält keinen Namen Heimrath. Zum ersten Male wird einer von ihnen im Zusammenhang mit einer Aufzeichnung aus dem Jahre 1645 im sogenannten Mirakelbuch der Aufkirchner Pfarrchronik namentlich erwähnt. Es heißt da, einer seiner Knechte habe sich in der Christnacht noch einmal im Stall bei den Pferden zu schaffen gemacht und dabei durch ein Guckloch in den dunklen, rauhreifüberzogenen Obstgarten geschaut.“

Cover

Zie voor de schrijvers van de 22 juli ook mijn blog van 22 juli 2018 deel 2.