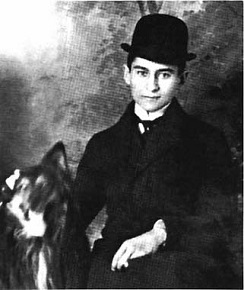

De Duitstalige schrijver Franz Kafka werd geboren op 3 juli 1883 in Praag, toen een stad gelegen in de dubbelmonarchie Oostenrijk-Hongarije. Zie ook alle tags voor Franz Kafka op dit blog.

Uit: Tagebücher 1910 – 1923

“Sonntag, den 19. Juli 1910, geschlafen, aufgewacht, geschlafen, aufgewacht, elendes Leben.

Variante

(…)

Der Vorwurf darüber, daß sie mir doch ein Stück von mir verdorben haben – ein gutes schönes Stück verdorben haben – im Traum erscheint es mir manchmal wie andern die tote Braut –, dieser Vorwurf, der immer auf dem Sprung ist, ein Seufzer zu werden, er soll vor allem unbeschädigt hinüberkommen, als ein ehrlicher Vorwurf, der er auch ist. So geschieht es, der große Vorwurf, dem nichts geschehen kann, nimmt den kleinen bei der Hand, geht der große, hüpft der kleine, ist aber der kleine einmal drüben, zeichnet er sich noch aus, wir haben es immer erwartet, und bläst zur Trommel die Trompete.

Oft überlege ich es und lasse den Gedanken ihren Lauf, ohne mich einzumischen, aber immer komme ich zu dem Schluß, daß mich meine Erziehung mehr verdorben hat, als ich es verstehen kann. In meinem Äußern bin ich ein Mensch wie andere, denn meine körperliche Erziehung hielt sich ebenso an das Gewöhnliche, wie auch mein Körper gewöhnlich war, und wenn ich auch ziemlich klein und etwas dick bin, gefalle ich doch vielen, auch Mädchen. Darüber ist nichts zu sagen. Noch letzthin sagte eine etwas sehr Vernünftiges: »Ach, könnte ich Sie doch einmal nackt sehn, da müssen Sie erst hübsch und zum Küssen sein.« Wenn mir aber hier die Oberlippe, dort die Ohrmuschel, hier eine Rippe, dort ein Finger fehlte, wenn ich auf dem Kopf haarlose Flecke und Pockennarben im Gesicht hätte, es wäre noch kein genügendes Gegenstück meiner innern Unvollkommenheit. Diese Unvollkommenheit ist nicht angeboren und darum um so schmerzlicher zu tragen. Denn wie jeder habe auch ich von Geburt aus meinen Schwerpunkt in mir, den auch die närrischste Erziehung nicht verrücken konnte. Diesen guten Schwerpunkt habe ich noch, aber gewissermaßen nicht mehr den zugehörigen Körper. Und ein Schwerpunkt, der nichts zu arbeiten hat, wird zu Blei und steckt im Leib wie eine Flintenkugel. Jene Unvollkommenheit ist aber auch nicht verdient, ich habe ihr Entstehn ohne mein Verschulden erlitten. Darum kann ich in mir auch nirgends Reue finden, soviel ich sie auch suche. Denn Reue wäre für mich gut, sie weint sich ja in sich selbst aus, sie nimmt den Schmerz beiseite und erledigt jede Sache allein wie einen Ehrenhandel; wir bleiben aufrecht, indem sie uns erleichtert.“

Franz Kafka (3 juli 1883 – 3 juni 1924)