De Franse schrijver André Gide werd geboren op 22 november 1869 in Parijs. Zie ook alle tags voor André Gide op dit blog.

Uit: Les Faux-monnayeurs

“Mais si cela voulait dire quelque chose, tu ne comprendrais tout de même pas.

Quand on parle, c’est pour se faire comprendre.

Veux-tu, nous allons jouer à faire des mots pour nous deux seulement les comprendre.

Tâche d’abord de bien parler français.

Ma maman, elle, parle le français, l’anglais, le romain, le russe, le turc, le polonais, l’italoscope, l’espagnol, le perruquoi et le xixitou.

Tout ceci dit très vite, dans une sorte de fureur lyrique.

Bronja se mit à rire.

Boris, pourquoi est-ce que tu me racontes tout le temps des choses qui ne sont pas vraies ?

Pourquoi est-ce que tu ne crois jamais ce que je te raconte ?

Je crois ce que tu me dis, quand c’est vrai.

(…)

Oui. Non ; écoute : on va prendre un bâton ; tu tiendras un bout et moi l’autre. Je vais fermer les yeux et je te promets de ne les rouvrir que quand nous serons arrivés là-bas.

Ils s’éloignèrent un peu ; et, tandis qu’ils descendaient les marches de la terrasse, j’entendis encore Boris :

Oui, non, pas ce bout-là. Attends que je l’essuie.

Pourquoi ?

J’y ai touché.”

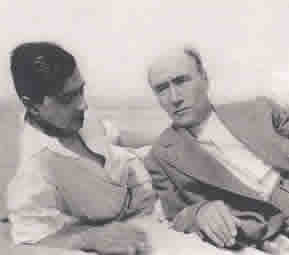

André Gide (22 november 1869 – 19 februari 1951)

Hier met zijn jonge geliefde Marc Allégret (links) in 1926