De Nederlandse dichter, schrijver en columnist Cees van der Pluijm werd geboren op 12 januari 1954 te Radio Kootwijk (Gld.). Zie ook alle tags voor Cees van der Pluijm op dit blog.

Filippino Lippi (1459-‑1504) ─ zelfportret

Zijn ogen zijn van stilte overtogen

En uit de open, welgevormde mond

Klinkt niets dat je verrukken kan of schokken ─

Hij lijkt een zwijgend kind van zestien jaar

Zijn zacht gelaat is jongensachtig rond

Voorzichtig springen hier en daar zijn lokken

Iets op uit de gekamde regelmaat

Van zijn in bruine lagen vallend haar

Toch ziet hij je met zijn verstarde ogen

Er broeit iets dat zich slechts beschrijven laat

Als niet onaangedaan en niet verveeld

Je hoort zijn stem in dit verstomde beeld

En proeft de hartstocht die hier onbewogen

Voor eeuwig in de kalk geschilderd staat

De kleine waterval

Het water maakt een lange reis

Nu valt het hier van het plateau

Waar even het de hoogte vond

En dan verzinkt als vloeibaar ijs

Ginds komt het wellend uit de grond

Passeert het slot en trapsgewijs

Verandert telkens het niveau

Zo gaat het heel de wereld rond

En keert terug waar het ontstond

En stroomt dan weer van ons vandaan

Ontspringen, zijn, ten ondergaan –

Wij stromen als het water mee

Het spiegelt ons vergeefs bestaan:

We drijven langzaamaan naar zee

Katholieke roman

Paul Lemmens S.J.

In ’t oude huis heerst droefenis en schrik

De bleke vader loopt vertwijfeld rond

Eenieder ziet zijn triest omfloerste blik

De zeven zoons, zij houden braaf hun mond

En ook de meisjes, negen in totaal

Ontzien hun lieve vader in deez’ stond

Want in de stille kamer, hoog en kaal

Ligt zij, de moeder van de kinderschaar

Nu opgebaard, haar lichaam koud als staal

Ze ligt, met zoete bloempjes in het haar

Als slapend op het bed dat werd tot baar

Cees van der Pluijm (12 januari 1954 – 14 december 2014)

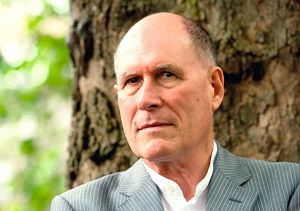

De Britse schrijver David Mitchell werd geboren in Southport op 12 januari 1969. Zie ook alle tags voor David Mitchell op dit blog.

Uit:Black Swan Green

“Do not set foot in my office. That’s Dad’s rule. But the phone’d rung twenty-five times. Normal people give up after ten or eleven, unless it’s a matter of life or death. Don’t they? Dad’s got an answering machine like James Garner’s in The Rockford Files with big reels of tape. But he’s stopped leaving it switched on recently. Thirty rings, the phone got to. Julia couldn’t hear it up in her converted attic ‘cause “Don’t You Want Me?” by Human League was thumping out dead loud. Forty rings. Mum couldn’t hear ‘cause the washing machine was on berserk cycle and she was hoovering the living room. Fifty rings. That’s just not normal. S’pose Dad’d been mangled by a juggernaut on the M5 and the police only had this office number ‘cause all his other I.D.’d got incinerated? We could lose our final chance to see our charred father in the terminal ward.

So I went in, thinking of a bride going into Bluebeard’s chamber after being told not to. (Bluebeard, mind, was waiting for that to happen.) Dad’s office smells of pound notes, papery but metallic too. The blinds were down so it felt like evening, not ten in the morning. There’s a serious clock on the wall, exactly the same make as the serious clocks on the walls at school. There’s a photo of Dad shaking hands with Craig Salt when Dad got made regional sales director for Greenland. (Greenland the supermarket chain, not Greenland the country.) Dad’s IBM computer sits on the steel desk. Thousands of pounds, IBMs cost. The office phone’s red like a nuclear hotline and it’s got buttons you push, not the dial you get on normal phones. So anyway, I took a deep breath, picked up the receiver, and said our number. I can say that without stammering, at least. Usually. But the person on the other end didn’t answer.

“Hello?” I said. “Hello?”

They breathed in like they’d cut themselves on paper.

“Can you hear me? I can’t hear you.”

Very faint, I recognized the Sesame Street music.

“If you can hear me”—I remembered a Children’s Film Foundation film where this happened—”tap the phone, once.”

There was no tap, just more Sesame Street.

“You might have the wrong number,” I said, wondering.

A baby began wailing and the receiver was slammed down.

When people listen they make a listening noise.

I’d heard it, so they’d heard me.

“May as well be hanged for a sheep as hanged for a handkerchief.” Miss Throckmorton taught us that aeons ago. ‘Cause I’d sort of had a reason to have come into the forbidden chamber, I peered through Dad’s razor-sharp blind, over the glebe, past the cockerel tree, over more fields, up to the Malvern Hills”.

David Mitchell (Southport, 12 januari 1969)

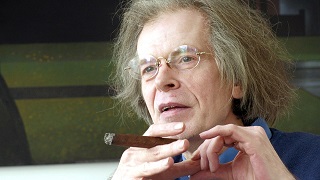

De Nederlandse dichter en schrijver Jacques Hamelink werd geboren op 12 januari 1939 in Driewegen, bij Terneuzen. Zie ook alle tags voor Jacques Hamelink op dit blog.

Het idee

De magnolia, voorloper,

verspilde zijn bloesems nog. Daarna kwam

in de koude wind de bosduif terug

van verleden jaar. Een nieuwe vestigingspoging –

het idee

geeft me je geneurie, onafgebroken,

dat niet zingt maar zacht stookt,

aanstuurt op zang.

De Moorse tuin

Als kind, je weet het, vond ik troost

bij de vlier die uitliep

langs de slootkant. Zijn verwarrende geur

werd tot chiffre van mijn folklore, hartzeer

dat zich hier hervindt. Voor het gevoel

wieg je, weerleg je mijn aarzeling nog weer

als gisteren, toen in de wrange wind

de oleander in bloei ging.

Ansicht

Dorre dag, fijn schuurzand dat ons gesloten heden

door kieren binnendringt; armetierig leven,

dat aan de basis ligt, dat ons slikt; doorgangshuis

voor de wind die hijgt naar de regen, de lathyrus losrukt

van de latten, tot vervelens toe je bloemperken rammeit

terwijl hier, in de tochtloze hemisfeer

van een huurkamer, een kitschpendule onder een stolp

werktuigelijk het museale begrip tijd intakt houdt.

Wat zei je ook weer, dat de wind ging liggen?

De weinige woorden hebben alle bijbetekenissen afgelegd,

hier kan niets meer gebeuren of gebeurt

bij het minste of het geringste alles opnieuw, zodra

een pauze valt onder de lamp, je polshorloge luider gaat tikken,

je je adem inhoudt, buiten

eindelijk de regen begint, een nachtvogel schreeuwt,

je bij vergissing misschien het gebaar vindt

dat aan zijn bedoeling beantwoordt.

Jacques Hamelink (Terneuzen, 12 januari 1939)

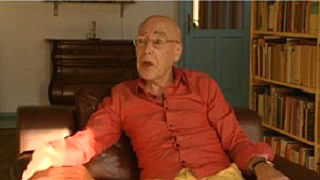

De Japanse schrijver en vertaler Haruki Murakami werd geboren op 12 januari 1949 in Kyoto. Zie ook alle tags voor Haruki Murakami op dit blog.

Uit: Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Vertaald door Philip Gabriel)

“One Saturday night, Tsukuru and Haida were up talking late as usual when they turned to the subject of death. They talked about the significance of dying, about having to live with the knowledge that you were going to die. They discussed it mainly in theoretical terms. Tsukuru wanted to explain how close to death he had been very recently, and the profound changes that experience had brought about, both physically and mentally. He wanted to tell Haida about the strange things he’d seen. But he knew that if he mentioned it, he’d have to explain the whole sequence of events, from start to finish. So as always, Haida did most of the talking, while Tsukuru sat back and listened.

A little past 11 p.m. their conversation petered out and silence descended on the room. At this point they would normally have called it a night and gotten ready for bed. Both of them tended to wake up early. But Haida remained seated, cross-legged, on the sofa, deep in thought. Then, in a hesitant tone, something unusual for him, he spoke up.

“I have a kind of weird story related to death. Something my father told me. He said it was an actual experience he had when he was in his early twenties. Just the age I am now. I’ve heard the story so many times I can remember every detail. It’s a really strange story—it’s hard even now for me to believe it actually happened— but my father isn’t the type to lie about something like that. Or the type who would concoct such a story. I’m sure you know this, but when you make up a story the details change each time you retell it. You tend to embellish things, and forget what you said before. … But my father’s story, from start to finish, was always exactly the same, each time he told it. So I think it must be something he actually experienced. I’m his son, and I know him really well, so the only thing I can do is believe what he said. But you don’t know my father, Tsukuru, so feel free to believe it or not. Just understand that this is what he told me. You can take it as folklore, or a tale of the supernatural, I don’t mind. It’s a long story, and it’s already late, but do you mind if I tell it?”

Sure, Tsukuru said, that would be fine. I’m not sleepy yet.”

Haruki Murakami (Kioto, 12 januari 1949)

De Nederlandse dichter en schrijver Kamiel Verwer werd op 12 januari 1979 in Tilburg geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Kamiel Verwer op dit blog.

Uit: Plezier met het CJIB

“Maar dat is toch vreemd. Het is al drie maanden geleden.”

– “Het kan soms wel langer duren.”

“Ik bel omdat ik misschien in de niet al te verre toekomst ga emigreren naar een land buiten Europa. Het adres dat ik aan de agenten heb opgegeven is dan niet meer geldig. Wat gebeurt er wanneer de brief de afzender niet kan bereiken?”

– “Dat hangt ervan af.”

“Stel: ik kom over twintig jaar terug naar Nederland om afscheid te nemen van een doodziek familielid. Wat gebeurt er wanneer die boete nog open staat?”

– “Dat zou ik u niet kunnen zeggen.”

“Mooi. Dat is belangrijk voor me om te weten.”

– “Het hangt van de beslissing van de politie over twintig jaar af. U zou bijvoorbeeld kunnen worden aangehouden.”

“Aangehouden? Zou ik in de cel kunnen worden gezet?”

– “Dat behoort eventueel ook tot de mogelijkheden, ja.”

“Goed zo. En in die cel wordt me ook nooit duidelijk gemaakt waar ik precies aan toe ben?”

– “Maakt u zich maar geen zorgen, meneer Verwer.”

“Prachtig. Er zijn nog een paar kleine dingetjes die ik wil weten.”

– “Vraagt u maar. We zijn er om u te helpen.”

“Stel dat ik bij u langskom aan de balie, en dan de boete direct betaal. Dat scheelt u weer een brief en…”

– “Helaas hebben wij geen bezoekadres.”

“Prima! Dat is waar ik stiekem op had gehoopt.”

– “Ik ben blij dat ik u van dienst heb kunnen zijn. Heeft u verder nog vragen?”

“Heeft u enig idee om wat voor boete het gaat?”

– “Daarvoor zou ik u moeten doorverbinden naar een andere afdeling.”

“Dit is schitterend. Dank u wel!”

– “Een prettige middag nog, meneer Verwer.”

Kamiel Verwer (Tilburg, 12 januari 1979)

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz werd geboren op 12 januari 1751 in Seßwegen. Zie ook alle tags voor Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz op dit blog.

Das Vertrauen auf Gott

Ich weiß nichts von Angst und Sorgen,

Denn, erwach’ ich jeden Morgen,

Seh’ ich, daß mein Gott noch lebt,

Der die ganze Welt belebt.

Dem hab’ ich mich übergeben,

Er mag auf mich Achtung geben,

Er ist Vater, ich das Kind,

Meinem Vater folg’ ich blind.

Ich bins so gewohnt von Langem,

Unverrückt an ihm zu hangen.

Wo ich bin, da ist auch er,

Wenn es auch bei’m Teufel wär’.

Toben Stürme, Unglücks-Wellen,

Wenn die Feinde noch so bellen,

Bin ich ruhig, denn mein Gott

Half mir noch aus aller Noth.

Und wenn auch die Noth am größten,

Eben recht, so dient’s am besten:

Wenn die Wege wunderlich,

Gehn sie immer seliglich.

Wenn du willst an Ihm verzagen,

Dich mit eitlen Sorgen plagen,

Ei so sag’ nicht, daß du bist

Gotteskind, ein wahrer Christ.[12]

Der aus Nichts die Welten machte

Unser Gott im Himmel sagte:

Ruf’ mich an, so führ’ ich dich,

Helf’ dir, und errette dich.

Gott hat Jesum uns gegeben,

Daß wir möchten durch Ihn leben:

Jesum, Seinen lieben Sohn,

Sandte Er vom Himmelsthron.

Er ist unser Fürst geworden,

Er soll helfen aller Orten,

Denen, die sich Seiner freu’n,

Und ihr Herz der Liebe weih’n.

Wird denn Der dich lassen sterben,

Der dich hat gesetzt zum Erben?

Der für dich geschmeckt den Tod?

Gott bleibt immer Gott, dein Gott!

Hoffe nun, steh’ fest im Glauben,

Laß dir nichts die Hoffnung rauben;

Ließe dich dein Fürst in Noth,

Würd’ Er selbst der Feinde Spott.

Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz (12 januari 1751- 24 mei 1792)

Cover

De Albanese schrijver Fatos Kongoli werd geboren op 12 januari 1944 in Elbasan. Zie ook alle tags voor Fatos Kongoli op dit blog.

Uit: The Loser (Vertaald door Robert Elsie en Janice Mathie-Heck)

“All of a sudden I turned and bolted. Vilma stood there at the fence with Max. Years later, she reminded me of the scene. ‘You were so strange, the way you stared at me, looking right into my eyes! I went back to the stairs with Max and pretended I was reading, but actually I was waiting for you to come back and stare into my eyes again. No boy had ever looked at me that way and I didn’t understand what it was that made me wait for you. I never stopped believing that you’d reappear at the fence one day, even later when you were going to university and rumours had spread in town that you were having an affair with a widow. But you never turned up. I waited for you, even though you poisoned my Max. I cried for him as I would have for a brother. And yet, I waited for you, though I was convinced you’d never come back.’

From the moment I started to run, I was convinced, too, that I wouldn’t go back. When Vilma picked Max up and started to talk to me, I knew that if I stayed any longer, I wouldn’t be able to take revenge at all. I don’t know how to explain it properly, but I felt that if I hung around near Vilma, listening to her voice, looking into her eyes and watching her pet the dog, I wouldn’t feel up to poisoning Max. And if I didn’t poison Max, Vilma wouldn’t cry. And if Vilma didn’t cry, Xhoda wouldn’t lose his mind.

Max had a painful but quick end. Before we committed the crime, Sherif asked me to find out what food the dog preferred. With some trouble, I found out from a boy who used to visit Vilma quite often – they were cousins – that Max loved fried liver, preferably lamb. I got some. Without his father noticing, Sherif mixed it with the poison used to exterminate wild dogs. We did away with Max one afternoon while Vilma was taking him out for a walk, as she often did, to the edge of town where the fields start.”

Fatos Kongoli (Elbasan, 12 januari 1944)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 12e januari ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.