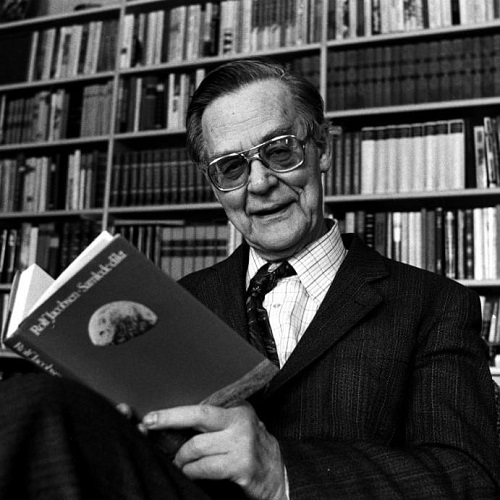

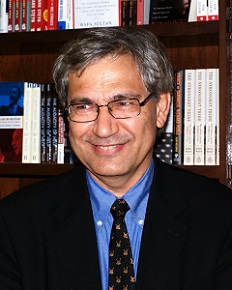

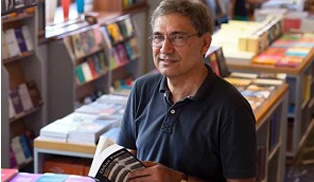

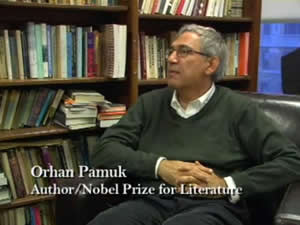

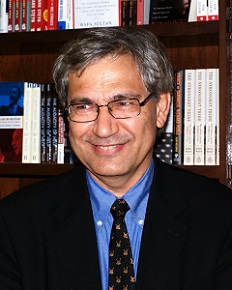

De Turkse schrijver Orhan Pamuk werd geboren op 7 juni 1952 in Istanbul. Zie ook alle tags voor Orhan Pamuk op dit blog.

Uit: The Red-Haired Woman (Vertaald door Ekin Oklap)

“The settlement was fifteen minutes on foot from our well. It was the town of Öngören, population 6,200, according to the blue sign with enormous white letters marking the entrance. After two days of ceaseless digging, two meters, we took a break on the second afternoon and went down to Öngören to acquire more supplies.

Ali took us to the town carpenter first. Having dug past two meters, we could no longer shovel out the earth by hand, so like all welldiggers, we had to build a windlass. Master Mahmut had brought some lumber in the landowner’s pickup, but it wasn’t enough. When he explained who we were and what we were up to, the inquisitive carpenter said, “Oh, you mean that land up there!”

Over the following days, whenever we went down to the town from “that land up there,” Master Mahmut made a point of dropping by the carpenter; the grocer, who sold cigarettes; the bespectacled tobacconist; and the ironmonger, who stayed open late. After digging all day, I relished going to Öngören with Master Mahmut for an evening stroll by his side, or to sit in the shade of the cypress and pine trees on some little bench, or at a table outside some coffeehouse, on the stoop of some shop, or in the train station.

It was Öngören’s misfortune to be overrun by soldiers. An infantry battalion had been stationed there during World War II to defend Istanbul against German attacks via the Balkans, and Russian attacks via Bulgaria. That purpose, like the battalion itself, was soon forgotten. But forty years later, the unit was still the town’s greatest source of income, and its curse.

Most of the shops in the town center sold postcards, socks, telephone tokens, and beer to soldiers on day passes. The stretch known among locals as Diners’ Lane was lined with various eateries and kebab shops, also catering to the military clientele. Surrounding them were pastry shops and coffeehouses that would be jammed with soldiers during the day—especially on weekends—but in the evenings, when these places emptied out, a completely different side of Öngören emerged. The gendarmes, who patrolled the area vigilantly, would have to pacify carousing infantrymen and break up fistfights among privates, in addition to restoring the peace disturbed by boisterous civilians or by the music halls when the entertainment got too loud.“

Orhan Pamuk (Istanbul, 7 juni 1952)

De Duitse schrijfster Monika Mann werd als vierde kind van Thomas Mann geboren op 7 juni 1910 in München. Zie ook alle tags voor Monika Mann op dit blog.

Uit: Das fahrende Haus

„Fast ohne Unterbrechung zwölf Jahre in einem Land gelebt zu haben – soll ich sagen, daß es die besten Jahre waren? –, reichen aus, ihm Treue und Verbundenheit zu bewahren fürs Leben.

Ein Gesetz der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika jedoch erlaubt ihrem naturalisierten Bürger nicht mehr als fünf Jahre seiner ununterbrochenen Abwesenheit. Überschreitet er diese Frist, verliert er die Staatsbürgerschaft. Wer aber will den Kontinent so mir nichts, dir nichts wechseln, noch dazu um eines Gesetzes willen, das unserer Zeit entwachsen, nicht würdig scheint? Denn in Europa leben, heißt nicht, fern von Amerika leben, heißt nicht, das verlernen und vergessen, was man in der Neuen Welt gelernt und erfahren und sich errungen hat. Die Länder Europas, sind sie nicht so etwas wie amerikanische Provinzen (nicht zu ihrer Schande sei’s gefragt!), und sind die Vereinigten Staaten Amerikas nicht so etwas wie europäische Ableger? Leben wir nicht in einer Welt, die immer mehr zusammenrückt, die unvermeidlich, bei allem Zaudern und Widerstand sich vereinheitlicht und vereinigt? Während ich meine amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft niederlege, lese ich Emerson und Whitman, schreibe ich meine «Amerikanische Novelle», denk’ ich an zwölf, wenn nicht immer leichte, so doch helle Jahre in New York und Los Angeles, New England, Vermont und Maine . . . Ja, es ist vor allem Amerikas Licht, das so unvergeßlich ist. Der Himmel der Neuen Welt ist heller als der Himmel der Alten Welt. (Ein grüner Baum wirkt dort dunkler als hier, zuweilen fast schwarz gegen das lichte Blau.)”

Monika Mann (7 juni 1910 – 17 maart 1992)

Thomas en Monika Mann, rond 1940

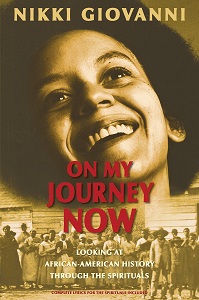

De Amerikaanse dichteres en schrijfster Nikki Giovanni werd geboren op 7 juni 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee. Zie ook alle tags voor Nikki Giovanni op dit blog.

A Historical Footnote to Consider Only When All Else Fails

(For Barbara Crosby)

While it is true

(though only in a factual sense)

That in the wake of a

Her-I-can comes a

Shower

Surely I am not

The gravitating force

that keeps this house

full of panthers

Why, LBJ has made it

quite clear to me

He doesn’t give a

Good goddamn what I think

(else why would he continue to masterbate in public?)

Rhythm and Blues is not

The downfall of a great civilization

And I expect you to

Realize

That the Temptations

have no connection with

The CIA

We must move on to

the true issues of

Our time

like the mini-skirt

Rebellion

And perhaps take a

Closer look at

Flour power

It is for Us

to lead our people

out of the

Wein-Bars

into the streets

into the streets

(for safety reasons only)

Lord knows we don’t

Want to lose the

support

of our Jewish friends

So let us work

for our day of Presence

When Stokely is in

The Black House

And all will be right with

Our World

Nikki Giovanni (Knoxville, 7 juni 1943)

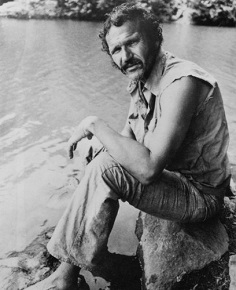

De Amerikaanse schrijver Harry Crews werd geboren op 7 juni 1935 in Bacon County, Georgia. Zie ook alle tags voor Harry Crews op dit blog.

Uit: Classic Crews: A Harry Crews Reader

“He was smiling, but he’d said it with just the finest edge of contempt, which is the way you are supposed to say it, and I scrambled to follow him, my heart lifting. Byron had heard me ask him much the same thing many times before, because if you change a couple of words, the question will serve in any number of circumstances. And now, in great high spirits, he was giving it back to me. …

“Dad, you remember about the time with the rain?”

“The time about the rain? Hell, son, we been in the rain a lot together.” I was wet and my feet hurt. I wanted to get the tent up and start a fire.

He cut his eyes toward me. Drops of rain hung on the ends of his fine lashes. He was suddenly very serious. What in the hell was coming down here? What was coming down was the past that is never past and, in this case, the past against which I had no defense except my own failed heart.

“We weren’t in it together,” he said. “You made me stand in it. Stand in it for a long time.”

Yes, I had done that, but I had not thought about it in years. It’s just not the sort of thing a man would want to think about. Byron’s mother had gone North for a while and left me to take care of him. He was seven years old and just starting in the second grade. I had told him that day to be home at six o’clock and we should go out to dinner. Truthfully, we’d been out to eat every night since Sally had been gone, because washing dishes is right up at the top of the list of things I won’t do. It had started misting rain at midday and had not stopped. Byron had not appeared at six, nor was he there at 6:45. That was back when I was bad to go to the bottle, and while I wasn’t drunk, I wasn’t sober, either. Lay it on the whiskey. A man will snatch at any straw to save himself from the responsibility of an ignoble action. When he did come home at 7:15, I asked him where he’d been.

“At Joe’s,” he said. But I had known that. I reminded him of when we had said we were going to dinner. But he had known that.

“It was raining,” he said.

I said, “Let’s go out and look at it.”

We went out into the carport and watched the warm spring rain.”

Harry Crews (7 juni 1935 – 28 maart 2012)

De Amerikaanse dichteres en schrijfster Louise Erdrich werd geboren op 7 juni 1954 in Little Falls, Minnesota. Zie ook alle tags voor Louise Erdrich op dit blog.

The King of Owls

It is said that playing cards were invented in 1392 to cure the French king, Charles VI, of madness. The suits in some of the first card packs consisted of Doves, Peacocks, Ravens, and Owls.

They say I am excitable! How could

I not scream? The Swiss monk’s tonsure

spun till it blurred yet his eyes were still.

I snapped my gaiter, hard, to stuff back

my mirth. Lords, he then began to speak.

Indus catarum, he said, presenting the game of cards

in which the state of the world is excellent described

and figured. He decked his mouth

as they do, a solemn stitch, and left cards

in my hands. I cast them down.

What need have I for amusement?

My brain’s a park. Yet your company

plucked them from the ground and began to play.

Lords, I wither. The monk spoke right,

the mealy wretch. The sorry patterns show

the deceiving constructions of your minds.

I have made the Deuce of Ravens my sword

falling through your pillows and rising,

the wing blades still running

with the jugular blood. Your bodies lurch

through the steps of an unpleasant dance.

No lutes play. I have silenced the lutes!

I keep watch in the clipped, convulsed garden.

I must have silence, to hear the messenger’s footfall

in my brain. For I am the King of Owls.

Where I float no shadow falls.

I have hungers, such terrible hungers, you cannot know.

Lords, I sharpen my talons on your bones.

Louise Erdrich (Little Falls, 7 juni 1954)

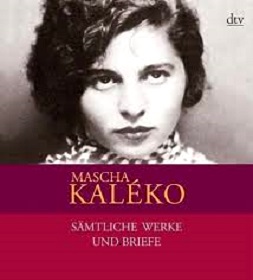

De Duitstalige dichteres Mascha Kaléko (eig. Golda Malka Aufen) werd geboren op 7 juni 1907 in Krenau of Schidlow in Galicië in het toenmalige Oostenrijk-Hongarije, nu Polen. Zie ook alle tags voor Mascha Kaléko op dit blog.

Langschläfers Morgenlied

Der Wecker surrt. Das alberne Geknatter

Reißt mir das schönste Stück des Traums entzwei.

Ein fleißig Radio übt schon sein Geschnatter.

Pitt äußert, daß es Zeit zum Aufstehn sei.

Mir ist vor Frühaufstehern immer bange.

… Das können keine wackern Männer sein:

Ein guter Mensch schläft meistens gern und lange.

– Ich bild mir diesbezüglich etwas ein …

Das mit der goldgeschmückten Morgenstunde

Hat sicher nur das Lesebuch erdacht.

Ich ruhe sanft. – Aus einem kühlen Grunde:

Ich hab mir niemals was aus Gold gemacht.

Der Wecker surrt. Pitt malt in düstern Sätzen

Der Faulheit Wirkung auf den Lebenslauf.

Durchs Fenster hört man schon die Autos hetzen.

– Ein warmes Bett ist nicht zu unterschätzen.

… Und dennoch steht man alle Morgen auf.

Mascha Kaléko (7 juni 1907 – 21 januari 1975)

Cover

De Nederlandse dichter Johannes Aloysius Antonius Engelman werd geboren in Utrecht op 7 juni 1900. Zie ook alle tags voor Jan Engelman op dit blog.

Gebed in ’t Duister

Heer, behoed haar in de wereld

die ik lang mijn eigen noem.

In haar ogen staat bepereld

met uw eigen dauw de bloem

van een onverwelkbaar minnen

uit de grond der ziel geteeld.

En geen stervling zal bezinnen

op het eeuwig Aanvangsbeeld

lijk uw knecht, die hare leden

in het schemerlicht onthult,

die zich, stamelend gebeden,

aan háár wil alleen vervult.

Lang voor ’t eerste dagegloren,

lang na Venus’ gouden schijn

kniel ik, uwe stem te horen

uit die weelde, uit die pijn,

uit die tuin, bedekt, bedwereld

met een bloesem van Voorheen.

Heer, behoed haar in de wereld,

doe uw mantel om ons heen!

Klein Air

Morgen drink ik rode wijn,

morgen zal mijn lief hier zijn.

In de warme lampeschijn

zal zij liggen, bleek en fijn.

Wilder dan een springfontein

breek ik uit, en ben weer klein

bij haar leden, zoet satijn,

diepe bedding, dieper pijn.

Morgen drink ik rode wijn,

morgen zal mijn lief hier zijn.

Jan Engelman (Utrecht 7 juni 1900 ;Amsterdam 20 maart 1972)

Engelman helemaal links tijdens de uitreiking van de ANWB-prijs 1958

De Amerikaanse dichteres Gwendolyn Brooks werd geboren op 7 juni 1917 in Topeka, Kansas. Zie ook alle tags voor Gwendolyn Brooks op dit blog.

Speech To The Young : Speech To The Progress-Toward

Say to them,

say to the down-keepers,

the sun-slappers,

the self-soilers,

the harmony-hushers,

“even if you are not ready for day

it cannot always be night.”

You will be right.

For that is the hard home-run.

Live not for battles won.

Live not for the-end-of-the-song.

Live in the along.

The Good Man

The good man.

He is still enhancer, renouncer.

In the time of detachment,

in the time of the vivid heather and affectionate evil,

in the time of oral

grave grave legalities of hate – all real

walks our prime registered reproach and seal.

Our successful moral.

The good man.

Watches our bogus roses, our rank wreath, our

love’s unreliable cement, the gray

jubilees of our demondom.

Coherent

Counsel! Good man.

Require of us our terribly excluded blue.

Constrain, repair a ripped, revolted land.

Put hand in hand land over.

Reprove

the abler droughts and manias of the day

and a felicity entreat.

Love.

Complete

your pledges, reinforce your aides, renew

stance, testament.

Gwendolyn Brooks (7 juni 1917 – 3 december 2000)

In 1996

De Ierse schrijfster Elizabeth Bowen werd geboren op 7 juni 1899 in Dublin. Zie ook alle tags voor Elizabeth Bowen op dit blog.

Uit: Friends and Relations

“Now the service was over the afternoon steadily brightened. The open-sided marquee was not, after all, to prove a fiasco. Laurel and Edward, obedient to Mrs Studdart’s instructions, took up their position in the morning-room. A playing-card, overlooked, lay face down on the carpet. Edward stooped for it – ‘Don’t!’ she cried, ‘leave it!’ her heart in her mouth. Better not – Finding themselves still alone Edward and she kissed hastily, with a feverish calm. They had all time, but only the moment. Then Laurel arranged her train in a pool, as she had seen brides do. Mrs Studdart, coming in shortly afterwards, re-arranged it.

‘You might hold your lilies,’ said Mrs Studdart, who had discovered the sheaf on a hall table specially cleared for the top-hats.

‘Oh, Mother, I can’t; they’re heavy.’

‘But don’t you think it would be nice, Edward, if she were to hold her lilies?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Edward. ‘Do people generally?’

‘They’d be such a strain on one arm all the time. You see I can’t change them; I must keep my right arm for shaking hands.’

‘And shake hands lightly,’ said Mrs Studdart, ‘don’t grip.’

‘Did I look …?’

‘Lovely, lovely,’ said Mrs Studdart. She was looking round distractedly for a vase and soon found one, a kind of Italian urn in which she arranged the lilies beside the bride.

The house might have been designed for such an occasion. The position of the morning-room was admirable; it had two doors so that the guests could circulate through a chain of rooms. Each, having saluted the bridal pair, was to pass on through the dining-room; through the French window and out by duck-boards into the open- sided marquee. (This was the best of a summer wedding; to make this possible he and she had devoured each other nervously throughout the endless winter of their engagement.) In the dining-room Cousin Richard was to be posted to head the guests off through the window. He would be shot, he said, if he let one past him into the hall.

‘I shall depend upon you, Richard,’ said Mrs Studdart. (He had been in the Colonies.) ‘For if the two streams mix in the hall and people get squeezed back into the drawing-room and have to pass Laurel all over again, there will be the most shocking confusion.’

Elizabeth Bowen (7 juni 1899 – 22 februari 1973)

Cover

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 7e juni ook mijn blog van 7 juni 2015 deel 2.