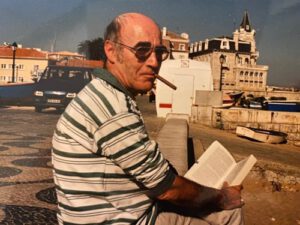

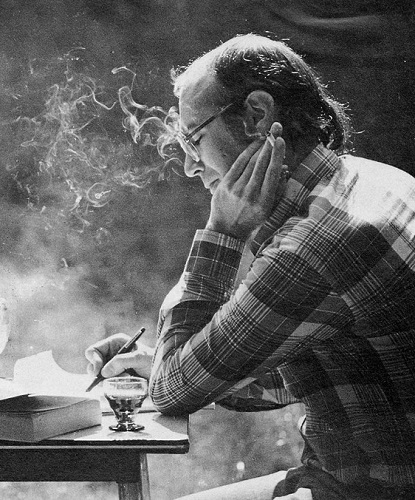

De Vlaamse dichter, essayist, journalist en tijdschriftuitgever Herman de Coninck werd geboren in Mechelen op 21 februari 1944. Zie ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

Nog een geluk dat

Zoals met de gek uit het grapje

die zich voortdurend met een hamer

op het hoofd sloeg, en naar de reden gevraagd, zei:

“Omdat het zo prettig is, als ik ermee ophou”-

zo is het een beetje met mij. Ik ben ermee opgehouden

je te verliezen. Ik ben je kwijt.

Misschien is dat geluk: een geluk bij een ongeluk.

Misschien is geluk: Nog een geluk dat.

Dat ik aan jou kan terugdenken, bv.,

in plaats van aan een ander.

Sneeuwstorm

In mijn streek zegt men ‘ver’ in de zin van

‘bijna’. Het is al ‘ver’ winter.

En zo ver is het inderdaad. Sneeuw is eeuwig leven

op een wit blad zonder letters geschreven,

niets is nog hier, alles is ginder.

Zoals dat boerderijtje, tien vadem

onder de sneeuw. Sneeuw doet het landschap

wat longen doen bij het inhouden van adem,

wat ik doe door niet te zeggen

hoe ik me tastend op alle plaatsen

en duizend keer per minuut en amechtig

en toch zoekend en bijna plechtig,

en lief en definitief, op jou wil neerleggen

als sneeuw, van de eerste vlok tot de laatste.

Vingerafdrukken op het venster

Ik denk dat poëzie iets is als vingerafdrukken

op het venster, waarachter een kind dat niet kan slapen

te wachten staat op de dag. Uit aarde komt nevel,

uit verdriet een soort ach. Wolken

zorgen voor vijfentwintig soorten licht.

Eigenlijk houden ze het tegen. Tegenlicht.

Het is nog te vroeg om nu te zijn. Maar de rivieren

vertrekken alvast. Ze hebben het geruis

uit de zilverfabriek van de zee gehoord.

Dochter naast me voor het raam. Van haar houden

is de gemakkelijkste manier om dit alles te onthouden.

Vogels vinden in de smidse van hun geluid

Herman de Coninck (21 februari 1944 – 22 mei 1997)

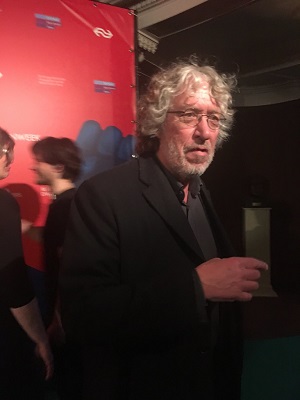

De Nederlandse dichter en prozaschrijver Hans Andreus werd geboren in Amsterdam op 21 februari 1926. Zie ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

Liggen in de zon

Ik hoor het licht het zonlicht pizzicato

de warmte spreekt weer tegen mijn gezicht

ik lig weer dat gaat zo maar niet dat gaat zo

ik lig weer monomaan weer monodwaas van licht.

Ik lig languit lig in mijn huid te zingen

lig zacht te zingen antwoord op het licht

lig dwaas zo dwaas niet buiten mensen dingen

te zingen van het licht dat om en op mij ligt.

Ik lig hier duidelijk zeer zuidelijk lig zonder

te weten hoe of wat ik lig alleen maar stil

ik weet alleen het licht van wonder boven wonder

ik weet alleen maar alles wat ik weten wil.

Liedje

Alle roekoemeisjes

van vanavond

alle toedoemeisjes

van vannacht

wat zeggen we daar nu wel van?

Niets.

We laten ze maar zitten

maar zitten maar liggen maar slapen

maar dromen van jaja.

Laatste gedicht

Dit wordt het laatste gedicht wat ik schrijf,

nu het met mijn leven bijna is gedaan,

de scheppingsdrift me ook wat is vergaan

met letterlijk de kanker in mijn lijf,

en, Heer (ik spreek je toch maar weer zo aan,

ofschoon ik me nauwelijks daar iets bij voorstel,

maar ik praat liever tegen iemand aan

dan in de ruimte en zo is dit wel

de makkelijkste manier om wat te zeggen),-

hoe moet het nu, waar blijf ik met dat licht

van mij, van jou, wanneer het vallen, weg in

het onverhoeds onnoemelijke begint ?

Of is het dat jij me er een onverdicht

woord dat niet uitgesproken hoeft voor vindt ?

Hans Andreus (21 februari 1926 – 9 juni 1977)

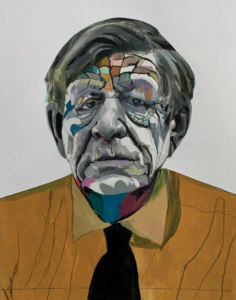

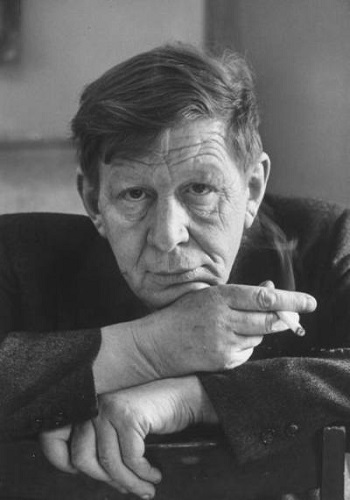

De Engelse dichter, essayist en criticus Wystan Hugh Auden werd geboren in York op 21 februari 1907. Zie ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

‘Op het feestje’

Het kletsen kent geen ritme, rijm of maat;

en toch hoort niemand proza in zijn praat.

De grondtoon onder al wat wordt ontvouwd

Zeurt monotoon dat men geen mens vertrouwt.

De namen van wie in de mode zijn

Blijken, ontcijferd, boodschappen van pijn.

Ik ben geen open boek waar je in kijkt.

Ik ben meer mij dan jij op iemand lijkt.

Is er geen hond die luistert naar mijn lied?

Ik ben wel bij je, maar daar blijf ik niet.

Een

schril en angstig huilen om gehoor

Snijdt door het volle penthouse, maar in koor

Praat iedereen slechts in zijn eigen oor.

Zet stil die klokken

Zet stil die klokken. Telefoon eruit.

Verbied de honden hun banaal geluid.

Sluit de piano’s, roep met stille trom

de laatste tocht van deze dode om.

Laat een klein vliegtuig boven ’t avondrood

de witte boodschap krassen: Hij is Dood.

Doe crêpepapier om elke duivenkraag

en hul de landmacht in het zwart, vandaag.

Hij was mijn Noord, mijn Zuid, mijn West en Oost,

hij was al mijn verdriet en al mijn troost,

mijn nacht, mijn middag, mijn gesprek, mijn lied,

voor altijd, dacht ik. Maar zo was het niet.

Laat in de sterren kortsluiting ontstaan,

maak ook de zon onklaar. Begraaf de maan.

Giet leeg die oceaan en kap het woud:

niets deugt meer, nu hij niet meer van mij houdt.

Vertaling door Willem Wilmink

Wystan Hugh Auden (21 februari 1907 – 29 september 1973)

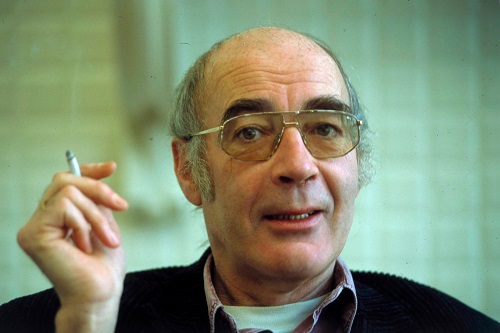

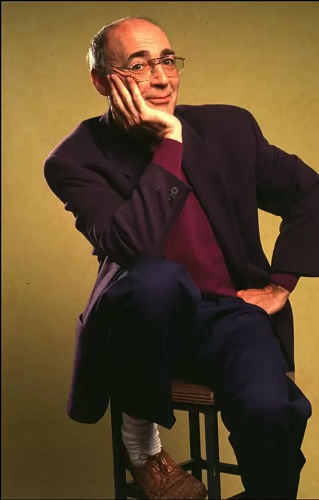

De Franse schrijver Raymond Queneau werd geboren op 21 februari 1903 in Le Havre. Zie ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

Uit: L’instand fatal

Si tu t’imagines

si tu t’imagines

fillette fillette

si tu t’imagines

xa va xa va xa

va durer toujours

la saison des za

la saison des za

saison des amours

ce que tu te goures

fillette fillette

ce que tu te goures

Si tu crois petite

si tu crois ah ah

que ton teint de rose

ta taille de guêpe

tes mignons biceps

tes ongles d’émail

ta cuisse de nymphe

et ton pied léger

si tu crois petite

xa va xa va xa va

va durer toujours

ce que tu te goures

fillette fillette

ce que tu te goures

les beaux jours s’en vont

les beaux jours de fête

soleils et planètes

tournent tous en rond

mais toi ma petite

tu marches tout droit

vers sque tu vois pas

très sournois s’approchent

la ride véloce

la pesante graisse

le menton triplé

le muscle avachi

allons cueille cueille

les roses les roses

roses de la vie

et que leurs pétales

soient la mer étale

de tous les bonheurs

allons cueille cueille

si tu le fais pas

ce que tu te goures

fillette fillette

ce que tu te goures

Raymond Queneau (21 februari 1903 – 25 oktober 1976)

De Franse schrijfster Anaïs Nin werd geboren op 21 februari 1903 in Neuilly. Zie ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

Uit: The Diaries

December 31 1919 *New Years Eve*

What a quiet way to await the beginning of another year! There must be many other things to think about that are more important than the passage of time, since so many other things stir our enthusiasm and drive us to act. That proves that Time doesn’t rule through the power of the Inevitable, and that the Inevitable isn’t Life.

There are the bells, the whistles. Happy New Year! Happy New Year!

JANUARY 16 1920

I am almost at the end of another notebook. But oh! how few adventures I will have written if nothing else happens before the last page! To be sure Maman is definately leaving for Cuba, but that is rather sad, and I always feel gloomy when she is going away.

Also, if I write so much everyday, I will not be able to tell you in here about my 17th birthday! I ought to shorten my chats, but I was born with a terribly long pen instead of a long tongue, and the dozens of letters I write seem like a drop in the water–I always want to write more!

If only you had a tongue, my little diary! You know that there was a sculptor who created a statue that came to life, and people made a snow-child that also came to life! From one moment to the next, I expect a little movement, a smile. I created you. Oh, become somebody!”

Anaïs Nin (21 februari 1903 – 14 januari 1977)

Zie voor onderstaande schrijvers ook mijn blog van 21 februari 2007.

De Spaanse dichteres Rosalía de Castro werd geboren op 21 februari 1837 in Santiago de Compostela.

De Nederlandse schrijver Justus van Effen werd geboren in Utrecht op 21 februari 1684.

‘

‘