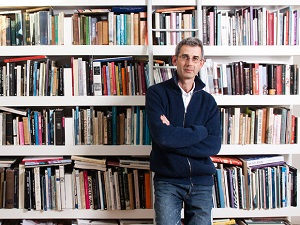

De Britse schrijver, keramist en hoogleraar Edmund Arthur Lowndes de Waal werd geboren op 10 september 1964 in Nottingham. De Waal is een zoon van de deken van Canterbury Cathedral, Victor de Waal. De Waal’s grootmoeder, Elisabeth de Waal, stamde uit de Weense, joodse familie Ephrussi. Ze trouwde met de Nederlander Hendrick de Waal en trol met hem door Europa om tijdens WO II tenslotte in Emgeland terecht te komen. Hij doorliep de King’s School in Canterbury voordat hij een beurs kreeg voor de studie Engels aan Trinity Hall in Cambridge. Tijdens zijn schooljaren in Canterbury de Waal leerde het ambacht van pottenbakker. Dus het was niet meer dan logisch dat hij na zijn afstuderen zijn eigen pottenbakkerij opende in het westen van Engeland in de buurt van de grens met Wales. Tegelijkertijd leerde hij de Japanse taal aan de Universiteit van Sheffield en kreeg een tweejarige werkbeurs van de stichting van het Japanse beursbedrijf Daiwa Shōken Group Honda, die hem in staat stelde om te werken in de Mejiro Ceramics Studio in Tokio. In 2010 werd de Waasl familiegeschiedenis “The Hare with the Amber Eyes: a Hidden Inheritance” gepubliceerd en in hetzelfde jaar won het boek de Costa Book Award in de categorie biografie. De titel verwijst naar een van de 264 Netsukefiguren die de Waal van zijn oudoom Iggy (Ignaz / Ignace) Leo Ephrussi had geërfd. Het verhaal beschrijft het leven van zijn voorouders, de joodse familie Ephrussi, die als Griekse Sephardim door handel en banktransacties in heel Europabekend werd, maar werden vervolgens echter als Joden werden vervolgd in de tijd van het nationaal-socialisme.

Uit: The Hare With Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance

“One sunny April day I set out to find Charles. Rue de Monceau is a long Parisian street bisected by the grand boulevard Malesherbes that charges off towards the boulevard Pereire. It is a hill of golden stone houses, a series of hotels playing discreetly on neoclassical themes, each a minor Florentine palace with heavily rusticated ground floors and an array of heads, caryatids and cartouches. Number 81 rue de Monceau, the Hôtel Ephrussi, where my netsuke start their journey, is near the top of the hill. I pass the headquarters of Christian Lacroix and then, next door, there it is. It is now, rather crushingly, an office for medical insurance.

It is utterly beautiful. As a boy I used to draw buildings like this, spending afternoons carefully inking in shadows so that you could see the rise and fall of the depth of the windows and pillars. There is something musical in this kind of elevation. You take classical elements and try to bring them into rhythmic life: four Corinthian pilasters rising up to pace the façade, four massive stone urns on the parapet, five storeys high, eight windows wide. The street level is made up of great blocks of stone worked to look as if they have been weathered. I walk past a couple of times and, on the third, notice that there is the double back-to-back E of the Ephrussi family incorporated into the metal grilles over the street windows, the tendrils of the letters reaching into the spaces of the oval. It is barely there. I try to work out this rectitude and what it says about their confidence. I duck through the passageway to a courtyard, then through another arch to a stable block of red brick with servants’ quarters above; a pleasing diminuendo of materials and textures.

A delivery man carries boxes of Speedy-Go Pizza into the medical insurers. The door into the entrance hall is open. I walk into the hall, its staircase curling up like a coil of smoke through the whole house, black cast iron and gold filigree stretching up to a lantern at the top. There is a marble urn in a deep niche, chequerboard marble tiles. Executives are coming down the stairs, heels hard on marble, and I retreat in embarrassment. How can I start to explain this idiotic quest? I stand in the street and watch the house and take some photographs, apologetic Parisians ducking past me. House-watching is an art. You have to develop a way of seeing how a building sits in its landscape or streetscape. You have to discover how much room it takes up in the world, how much of the world it displaces. Number 81, for instance, is a house that cannily disappears into its neighbours: there are other houses that are grander, some are plainer, but few are more discreet.”

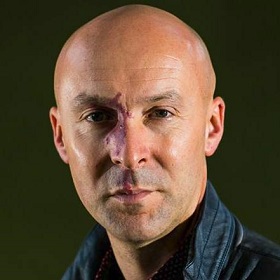

Edmund de Waal (Nottingham, 10 september 1964)