De Amerikaanse schrijver Colson Whitehead werd geboren op 6 november 1969 en groeide op in Manhattan. Hij bezocht de Trinity school in Manhattan en studeerde af aan Harvard University in 1991. Na het verlaten van de universiteit, schreef Whitehead voor The Village Voice. Tijdens het werken voor de Voice begon hij met het schrijven van zijn eerste romans. Whitehead heeft sindsdien zeven boeken gepubliceerd: zes romans en een meditatie over het leven in Manhattan in de stijl van E.B. White’s beroemde essay “Here Is New York”. Hij debuteerde in 1999 met “The Intuitionist”. Deze roman werd gevolgd door “John Henry Days”(2001), “The Colossus of New York” (2003) “Apex Hides the Hurt” (2006), “Sag Harbor” (2009), “Zone One, a New York Times Bestseller” (2011) en “The Underground Railroad” (2016) die hem de National Book Award for Fiction opleverde. Esquire Magazine noemde “The Intuitionist” het beste romandebuut van het jaar, en GQ noemde het boek een van de “romans van het millennium.” Whiteheads non-fictie, essays en recensies zijn verschenen in talrijke publicaties, waaronder The New York Times, The New Yorker, Granta, en Harper’s. Whitehead doceerde aan Princeton University, New York University, de University of Houston, Columbia University, Brooklyn College, Hunter College, Wesleyan University, en hij was writer-in-residence aan Vassar College, de Universiteit van Richmond en de Universiteit van Wyoming. In het voorjaar van 2015 begon hij in The New York Times Magazine een column over taal te schrijven. “The Underground Railroad” werd geselecteerd door Oprah’s Book Club 2.0 en werd ook door president Barack Obama gekozen als een van de vijf boeken op zijn lijst voor zijn zomervakantie.

Uit: Zone One

“He always wanted to live in New York. His Uncle Lloyd lived downtown on Lafayette, and in the long stretches between visits he daydreamed about living in his apartment. When his mother and father dragged him to the city for that season’s agreed-upon exhibit or good-for-you Broadway smash, they usually dropped in on Uncle Lloyd for a quick hello. These afternoons were preserved in a series of photographs taken by strangers. His parents were holdouts in an age of digital multiplicity, raking the soil in lonesome areas of resistance: a coffee machine that didn’t tell time, dictionaries made out of paper, a camera that only took pictures. The family camera did not transmit their coordinates to an orbiting satellite. It did not allow them to book airfare to beach resorts with close access to rain forests via courtesy shuttle. There was no prospect of video, high-def or otherwise. The camera was so backward that every lurching specimen his father enlisted from the passersby was able to operate it sans hassle, no matter the depth of cow-eyed vacancy in their tourist faces or local wretchedness inverting their spines. His family posed on the museum steps or beneath the brilliant marquee with the poster screaming over their left shoulders, always the same composition. The boy stood in the middle, his parents’ hands dead on his shoulders, year after year. He didn’t smile in every picture, only that percentage culled for the photo album. Then it was in the cab to his uncle’s and up the elevator once the doorman screened them. Uncle Lloyd dangled in the doorframe and greeted them with a louche “Welcome to my little bungalow.”

As his parents were introduced to Uncle Lloyd’s latest girlfriend, the boy was down the hall, giddy and squeaking on the leather of the cappuccino sectional and marveling over the latest permutations in home entertainment. He searched for the fresh arrival first thing. This visit it was the wireless speakers haunting the corners like spindly wraiths, the next he was on his knees before a squat blinking box that served as some species of multimedia brainstem. He dragged a finger down their dark surfaces and then huffed on them and wiped the marks with his polo shirt. The televisions were the newest, the biggest, levitating in space and pulsing with a host of extravagant functions diagrammed in the unopened owner’s manuals. His uncle got every channel and maintained a mausoleum of remotes in the storage space inside the ottoman. The boy watched TV and loitered by the glass walls, looking out on the city through smoky anti-UV glass, nineteen stories up.”

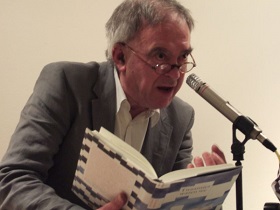

Colson Whitehead (New York, 6 november 1969)