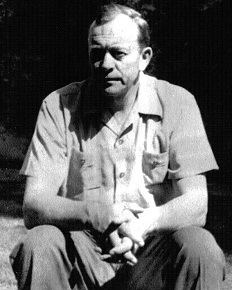

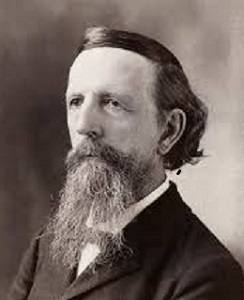

De Zuid-Afrikaanse schrijver André Brink werd geboren op 29 mei 1935 in Vrede. Zie ook alle tags voor André Brink op dit blog.

Uit: A dry white season

“Even if I’m hated, and ostracized, and persecuted, and in the end destroyed, nothing can make me black. And so those who are cannot but remain suspicious of me. In their eyes my very efforts to identify myself with Gordon, with all the Gordons, would be obscene. Every gesture I make, every act I commit in my efforts to help them makes it more difficult for them to define their real needs and discover for themselves their integrity and affirm their own dignity. How else could we hope to arrive beyond predator and prey, helper and helped, white and black, and find redemption?

On the other hand: what can I do but what I have done? I cannot choose not to intervene: that would be a denial and a mockery not only of everything I believe in, but of the hope that compassion may survive among men. By not acting as I did I would deny the very possibility of that gulf to be bridged.

If I act, I cannot but lose. But if I do not act, it is a different kind of defeat, equally decisive and maybe worse. Because then I will not even have a conscience left.

The end seems ineluctable: failure, defeat, loss. The only choice I have left is whether I am prepared to salvage a little honour, a little decency, a little humanity — or nothing. It seems as if a sacrifice is impossible to avoid, whatever way one looks at it. But at least one has the choice between a wholly futile sacrifice and one that might, in the long run, open up a possibility, however negligible or dubious, of something better, less sordid and more noble, for our children…”

André Brink (29 mei 1935 – 6 februari 2015)

Begin jaren 1960

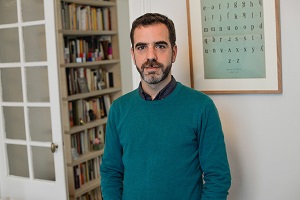

De Catalaanse dichter, schrijver en vertaler Eduard Escoffet werd geboren op 29 mei 1979 in Barcelona. Zie ook alle tags voor Eduard Escoffet op dit blog.

alles egal

die liebe

macht alles kaputt;

sie macht den sex kaputt,

sie zerstört den verstand

und sie bleicht den teint.

sie macht aus den augen ein möbel

und aus dem bett ein anderes möbel

– und zwar eins ums andere mal.

die liebe

macht das flirten kaputt,

sie tötet die masern,

sie tötet den schweifenden blick und

erhöht die moral

hin zu unbekannten neigungen.

die liebe

macht alles kaputt;

sie lässt die stimme rostig werden,

zerstört pläne und panoramablicke,

sie füllt den kaffee mit klumpen und

die adern mit nervenfasern, die sich überschlagen.

die liebe lässt das meer ruhig werden und die landschaften zahmer,

sie lässt die plattfüße platt

und macht platt die härteste rute.

die liebe

macht alles kaputt:

sie bedeckt dir die augen,

und zwischen den vorhängen und fensterläden

vergesse ich mich selbst,

die flüsse sind immer noch flüsse

und ich weiß nicht mehr was tun.

Vertaald doorRoger Friedlein

Eduard Escoffet (Barcelona, 29 mei 1979)

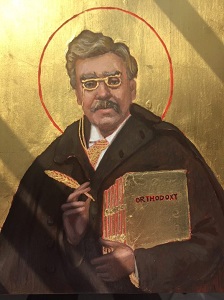

De Engelse dichter, letterkundige, schrijver en journalist Gilbert Keith Chesterton werd geboren in Londen op 29 mei 1874. Zie ook alle tags voor G. K. Chesterton op dit blog.

Uit: The Secret Garden (The Complete “Father Brown”)

“I mean,” said little Father Brown, from the corner of the room, “I mean that cigar Mr. Brayne is finishing. It seems nearly as long as a walking-stick.”

Despite the irrelevance there was assent as well as irritation in Valentin’s face as he lifted his head.

“Quite right,” he remarked sharply. “Ivan, go and see about Mr. Brayne again, and bring him here at once.”

The instant the factotum had closed the door, Valentin addressed the girl with an entirely new earnestness.

“Lady Margaret,” he said, “we all feel, I am sure, both gratitude and admiration for your act in rising above your lower dignity and explaining the Commandant’s conduct. But there is a hiatus still. Lord Galloway, I understand, met you passing from the study to the drawing-room, and it was only some minutes afterwards that he found the garden and the Commandant still walking there.”

“You have to remember,” replied Margaret, with a faint irony in her voice, “that I had just refused him, so we should scarcely have come back arm in arm. He is a gentleman, anyhow; and he loitered behind—and so got charged with murder.”

“In those few moments,” said Valentin gravely, “he might really—”

The knock came again, and Ivan put in his scarred face.

“Beg pardon, sir,” he said, “but Mr. Brayne has left the house.”

“Left!” cried Valentin, and rose for the first time to his feet.

“Gone. Scooted. Evaporated,” replied Ivan in humorous French. “His hat and coat are gone, too, and I’ll tell you something to cap it all. I ran outside the house to find any traces of him, and I found one, and a big trace, too.”

“What do you mean?” asked Valentin.

“I’ll show you,” said his servant, and reappeared with a flashing naked cavalry sabre, streaked with blood about the point and edge. Everyone in the room eyed it as if it were a thunderbolt; but the experienced Ivan went on quite quietly:

“I found this,” he said, “flung among the bushes fifty yards up the road to Paris. In other words, I found it just where your respectable Mr. Brayne threw it when he ran away.”

There was again a silence, but of a new sort. Valentin took the sabre, examined it, reflected with unaffected concentration of thought, and then turned a respectful face to O’Brien. “Commandant,” he said, “we trust you will always produce this weapon if it is wanted for police examination. Meanwhile,” he added, slapping the steel back in the ringing scabbard, “let me return you your sword.”

G. K. Chesterton (29 mei 1874 – 14 juli 1936)

Mark Williams speelt Father Brown in de BBC-serie vanaf 2013

De Franse schrijver Bernard Charles Henri Clavel werd geboren op 29 mei 1923 in Lons-le-Saunier. Zie ook alle tags voor Bernard Clavel op dit blog.

Uit: Les roses de Verdun

« Je suis allé à la porte. La neige tenait. La rue n’était pas déblayée et la voiture de Mme Vallier garée le long du trottoir, un peu plus bas, dans un renfoncement, était blanche. J’ai pensé un instant à la nettoyer, mais comme je ne savais pas quelle décision serait prise, je me suis dit que c’était inutile. Heureusement, elle était venue avec leur plus grosse auto qui était une quinze-chevaux Citroën. Si nous devions partir, sur la neige, la traction avant nous serait très précieuse. Et c’est une voiture que j’aime beaucoup conduire. […]

Ce matin-là encore Monsieur allait m’étonner. Alors que je m’attendais à l’entendre pester contre le mauvais sort qui semblait s’acharner sur nous depuis le début du voyage, lorsqu’il a vu tomber la neige il nous a déclaré:

– Quelle chance que l’Hotchkiss soit cassée, nous serons plus en sécurité dans la traction avec une route pareille.

Mais, au petit déjeuner, il y a eu un très vif accrochage entre les deux femmes et lui. En dépit de l’état des routes et de la piètre visibilité, il s’était mis en tête de pousser jusqu’à Aulnois. Ce qui représentait, en comptant le retour, pas loin de quatre cents kilomètres de plus. Ça me semblait à proprement parler de la folie pure. Fort heureusement, cette empoignade avait dû faire monter sa tension artérielle. Il est devenu rouge et son souffle, de nouveau court et saccadé, l’a obligé à se taire.

– Veux-tu que j’appelle le médecin? a demandé Madame.

Dans un grand effort qui faisait un peu mal à voir car la souffrance se lisait sur ses traits, il est parvenu à gronder:

– Fous-moi la paix avec ce con! Il t’a fait acheter pour une fortune de drogues à foutre aux chiottes… Il doit toucher des ristournes du pharmacien, celui-là… Entre les toubibs qui ne font rien et ceux qui font trop… Les malades qui s’en tirent ont vraiment la peau dure…

– Tais-toi, papa. Tu parles trop. Tu t’essouffles encore plus.

Sa fille lui a pris la main qu’elle a caressée tendrement. Elle lui ressemble. Mince et les traits un peu durs comme lui. Le même grand front. Elle a ajouté d’une voix très douce:

– Tu devrais aller te reposer un moment. Nous ferons les valises et, dès que des voitures auront circulé un peu, on essaiera de partir. S’il faut s’arrêter en route, ce ne sont pas les hôtels qui manquent, entre ici et Lyon. «

Bernard Clavel (29 mei 1923 – 5 oktober 2010)

Cover

De Engelse dichter en schrijver Terence Hanbury White werd geboren op 29 mei 1906 in Bombay (Mombai). Zie ook alle tags voor T. H. White op dit blog.

Uit:The Book of Merlyn

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlin, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That’s the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then — to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the only thing for you. Look what a lot of things there are to learn”.

(…)

“He caught a glimpse of that extraordinary faculty in man, that strange, altruistic, rare, and obstinate decency which will make writers or scientists maintain their truths at the risk of death. Eppur si muove, Galileo was to say; it moves all the same. They were to be in a position to burn him if he would go on with it, with his preposterous nonsense about the earth moving round the sun, but he was to continue with the sublime assertion because there was something which he valued more than himself. The Truth. To recognize and to acknowledge What Is. That was the thing which man could do, which his English could do, his beloved, his sleeping, his now defenceless English. They might be stupid, ferocious, unpolitical, almost hopeless. But here and there, oh so seldome, oh so rare, oh so glorious, there were those all the same who would face the rack, the executioner, and even utter extinction, in the cause of something greater than themselves. Truth, that strange thing, the jest of Pilate’s. Many stupid young men had thought they were dying for it, and many would continue to die for it, perhaps for a thousand years. They did not have to be right about their truth, as Galileo was to be. It was enough that they, the few and martyred, should establish a greatness, a thing above the sum of all they ignorantly had.”

T. H. White (29 mei 1906 – 17 januari 1964)

Cover

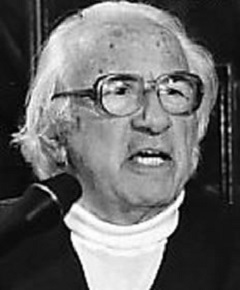

De Oostenrijkse schrijver en theatercriticus Hans Weigel werd geboren op 29 mei 1908 in Wenen. Zie ook alle tags voor Hans Weigel op dit blog.

Uit: Niemandsland

„Österreich nimmt den Untergang Österreichs nicht zur Kenntnis. Man hört hier auch schon das verhängnisvolle Wort vom “kleineren Übel”, das in Deutschland geprägt worden ist, so lange, bis die Betonung von dem “kleiner” unerheblich immer mehr auf “Übel” gewechselt hatte, so lange, bis das Übel unversehens immer grösser und schliesslich das ganz grosse geworden war. Peter versucht vergeblich darzutun, dass man jedes Übel bekämpfen müsse, ob es nun kleiner oder grösser sei.

Peter kann solche Gespräche nicht mehr hören. Es ist gespenstisch, höllisch, dass man hier das selbe erleben muss wie draussen, einen Staat auf dem selben Weg in den Untergang sehen und ein Volk die selben selbstbetrügerischen Phrasen dazu sagen hören muss, ohne dass man helfen kann, ja ohne dass der dokumentarische Hinweis dieser Gleichartigkeit auch nur zur Kenntnis genommen wird.

Peter fühlt sich erschöpft und völlig leer. Alles, was er, seit er denken kann, erlebt hat, alle Enttäuschung, alle Fragwürdigkeit seiner Existenz und der letzten Tage zumal, alles steigt auf, wächst unerträglich in ihm an und höhlt ihn aus. Kein Erlebnis kann ihn aus dieser Hoffnungslosigkeit reissen, was immer geschieht, wird sie nur bestätigen, falls es unerfreulich, wird sie doppelt grausam machen, wenn es erfreulich ist.“

Hans Weigel (29 mei 1908 – 12 augustus 1991)

Cover

De Argentijnse dichteres Alfonsina Storni werd geboren in Sala Capriasca, Zwitserland op 29 mei 1892. Zie ook alle tags voor Alfonsina Storni op dit blog.

You Want Me White

You want me to be the dawn

You want me made of seaspray

Made of mother-of-pearl

That I be a lily

Chaste above all others

Of tenuous perfume

A blossom closed

That not even a moonbeam

Might have touched me

Nor a daisy

Call herself my sister

You want me like snow

You want me white

You want me to be the dawn

You who had all

The cups before you

Of fruit and honey

Lips dyed purple

You who in the banquet

Covered in grapevines

Let go of your flesh

Celebrating Bacchus

You who in the dark

Gardens of Deceit

Dressed in red

Ran towards Destruction

You who maintain

Your bones intact

Only by some miracle

Of which I know not

You ask that I be white

(May God forgive you)

You ask that I be chaste

(May God forgive you)

You ask that I be the dawn!

Flee towards the forest

Go to the mountains

Clean your mouth

Live in a hut

Touch with your hands

The damp earth

Feed yourself

With bitter roots

Drink from the rocks

Sleep on the frost

Clean your clothes

With saltpeter and water

Talk with the birds

And set sail at dawn

And when your flesh

Has returned to you

And when you have put

Into it the soul

That through the bedrooms

Became entangled

Then, good man,

Ask that I be white

Ask that I be like snow

Ask that I be chaste

Vertaald door Catherine Fountain

Alfonsina Storni (29 mei 1892 – 25 oktober 1938)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Max Brand (eig. Frederick Schiller Faust) werd geboren op 29 mei 1892 in Seattle. Zie ook alle tags voor Max Brand op dit blog.

Uit: The Garden of Eden

“By careful tailoring the broad shoulders of Ben Connor were made to appear fashionably slender, and he disguised the depth of his chest by a stoop whose model slouched along Broadway somewhere between sunset and dawn. He wore, moreover, the first or second pair of spats that had ever stepped off the train at Lukin Junction, a glowing Scotch tweed, and a Panama hat of the color and weave of fine old linen. There was a skeleton at this Feast of Fashion, however, for only tight gloves could make the stubby fingers and broad palms of Connor presentable. At ninety-five in the shade gloves were out of the question, so he held a pair of yellow chamois in one hand and in the other an amber-headed cane. This was the end of the little spur-line, and while the train backed off down the track, staggering across the switch, Ben Connor looked after it, leaning upon his cane just forcibly enough to feel the flection of the wood. This was one of his attitudes of elegance, and when the train was out of sight, and only the puffs of white vapor rolled around the shoulder of the hill, he turned to look the town over, having already given Lukin Junction ample time to look over Ben Connor.

The little crowd was not through with its survey, but the eye of the imposing stranger abashed it. He had one of those long somber faces which Scotchmen call “dour.” The complexion was sallow, heavy pouches of sleeplessness lay beneath his eyes, and there were ridges beside the corners of his mouth which came from an habitual compression of the lips. Looked at in profile he seemed to be smiling broadly so that the gravity of the full face was always surprising. It was this that made the townsfolk look down. After a moment, they glanced back at him hastily. Somewhere about the corners of his lips or his eyes there was a glint of interest, a touch of amusement–they could not tell which, but from that moment they were willing to forget the clothes and look at the man.

While Ben Connor was still enjoying the situation, a rotund fellow bore down on him.

“You’re Mr. Connor, ain’t you? You wired for a room in the hotel? Come on, then. My rig is over here. These your grips?”

He picked up the suit case and the soft leather traveling bag, and led the way to a buckboard at which stood two downheaded ponies.”

Max Brand (29 mei 1892 – 12 mei 1944)

Cover

De Amerikaanse dichter, schrijver en publicist Joel Benton werd geboren op 29 mei 1832 in het kleine stadje Amenia, in county New York. Zie ook alle tags voor Joel Benton op dit blog.

The Scarlet Tanager

A all of fire shoots through the tamarack

In scarlet splendor, on voluptuous wings;

Delirious joy the pyrotechnist brings,

Who marks for us high summer’s almanac.

How instantly the red-coat hurtles back!

No fiercer flame has flashed beneath the sky.

Note now the rapture in his cautious eye,

The conflagration lit along his track.

Winged soul of beauty, tropic in desire,

Thy love seems alien in our northern zone;

Thou giv’st to our green lands a burst of fire

And callest back the fables we disown.

The hot equator thou mightst well inspire,

Or stand above some Eastern monarch’s throne.

Joel Benton (29 mei 1832 – 15 september 1911)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 29e mei ook mijn blog van 29 mei 2016 deel 2.