De Deense schrijver Jens Christian Grøndahl werd geboren in Lyngby op 9 november 1959. Zie ook alle tags voor Jens Christian Grøndahl op dit blog.

Uit: Often I Am Happy

“Now your husband is also dead, Anna. Your husband, our husband. I would have liked him to lie next to you, but you have neighbors, a lawyer and a lady who was buried a couple of years ago. The lawyer had been around for a long time when you joined them. I found a vacant plot for Georg on the next row; the back of his stone is visible from your grave. I opted for limestone, although the stonemason said it wouldn’t be weatherproof. So what? I don’t like granite. The twins would have liked granite—on this point they agreed for once. Granite is too heavy, and our Georg had been complaining about this weight on his chest. We should have taken it more seriously, but he shrugged it off. At first he moaned, and when you wanted to share his concern you were brushed aside. Georg was like that.

He collapsed in the shower. I knew right away that something was wrong, or only now I think I knew it. He groaned and it felt anomalous to maneuver his heavy, wet body. He was still conscious as I got him to bed. When the ambulance came, it was all over. He looked like himself, older but still nice enough. His belly was less protruding when he was lying on his back. You never saw him that way, but seventy-eight is nothing, really, don’t you agree? Or seventy, for that matter. It could have been you who found him on the tiles under the jet of hot water. Normally, it would have been you. Can you say that? He always stayed out there for so long. He might easily have remained standing if his coronary artery had not burst. It could have been your life continuing just like that. Where would I have been, in your life? Where would I have been in mine? I caressed him as we were waiting for the ambulance to come, but I don’t know if he felt anything. At some point as I sat with him, there was no longer anything to feel. I realized it later. He could not feel my touch, as if I were the one who was suddenly absent. His absence felt like a lump growing inside me, making me suffocate. I never felt so alone. One is used to reality responding or just resounding with whatever one thinks or feels. Death shuts up the living; the real is our enemy in the long run.

The day after the funeral, I biked to the cemetery again. I took a couple of the sprays and put them in front of your headstone. Otherwise, I have brought you flowers only when it was your birthday. The first years I came quite often, mostly alone. Georg didn’t like to come along, and in the end I’d stopped telling him that I had been at your grave. At that time, it had been ages since I’d stopped asking him why he wouldn’t come. I don’t think he ever forgave you completely, but even that he probably wouldn’t have wanted to admit, had I asked him. I might have construed his answer in the sense that I had not been fully capable of filling your place. He was so considerate, and I think he had come to be really fond of me. The years passed, mind you, and in the end we belonged together, simply because we lived side by side. We underestimate the power of habit while we’re young, and we underestimate the grace of it. Strange word, but there it is.”

Jens Christian Grøndahl (Lyngby, 9 november 1959)

De Russische schrijver Ivan Sergejevitsj Toergenjev werd geboren op 9 november 1818 in Orjol, in de Oekraïne. Zie ook alle tags voor Ivan Toergenjev op dit blog.

Uit: The District Doctor (Vertaald door Constance Garnett)

“One day in autumn on my way back from a remote part of the country I caught cold and fell ill. Fortunately the fever attacked me in the district town at the inn; I sent for the doctor. In half-an-hour the district doctor appeared, a thin, dark-haired man of middle height. He prescribed me the usual sudorific, ordered a mustard-plaster to be put on, very deftly slid a five-rouble note up his sleeve, coughing drily and looking away as he did so, and then was getting up to go home, but somehow fell into talk and remained. I was exhausted with feverishness; I foresaw a sleepless night, and was glad of a little chat with a pleasant companion. Tea was served. My doctor began to converse freely. He was a sensible fellow, and expressed himself with vigour and some humour. Queer things happen in the world: you may live a long while with some people, and be on friendly terms with them, and never once speak openly with them from your soul; with others you have scarcely time to get acquainted, and all at once you are pouring out to him — or he to you — all your secrets, as though you were at confession. I don’t know how I gained the confidence of my new friend — any way, with nothing to lead up to it, he told me a rather curious incident; and here I will report his tale for the information of the indulgent reader. I will try to tell it in the doctor’s own words.

‘You don’t happen to know,’ he began in a weak and quavering voice (the common result of the use of unmixed Berezov snuff); ‘you don’t happen to know the judge here, Mylov, Pavel Lukitch? . . . You don’t know him? . . . Well, it’s all the same.’ (He cleared his throat and rubbed his eyes.) ‘Well, you see, the thing happened, to tell you exactly without mistake, in Lent, at the very time of the thaws. I was sitting at his house — our judge’s, you know — playing preference. Our judge is a good fellow, and fond of playing preference. Suddenly’ (the doctor made frequent use of this word, suddenly) ‘they tell me, “There’s a servant asking for you.” I say, “What does he want?” They say, “He has brought a note — it must be from a patient.” “Give me the note,” I say. So it is from a patient — well and good — you understand — it’s our bread and butter. . . . But this is how it was: a lady, a widow, writes to me; she says, “My daughter is dying. Come, for God’s sake!” she says; “and the horses have been sent for you.” watercourses, and the dyke had suddenly burst there — that was the worst of it! However, I arrived at last. It was a little thatched house. There was a light in the windows; that meant they expected me. I was met by an old lady, very venerable, in a cap. “Save her!” she says; “she is dying.” I say, “Pray don’t distress yourself — Where is the invalid?” “Come this way.” I see a clean little room, a lamp in the corner; on the bed a girl of twenty, unconscious. She was in a burning heat, and breathing heavily — it was fever. There were two other girls, her sisters, scared and in tears. “Yesterday,” they tell me, “she was perfectly well and had a good appetite; this morning she complained of her head, and this evening, suddenly, you see, like this.” I say again: “Pray don’t be uneasy.” It’s a doctor’s duty, you know — and I went up to her and bled her, told them to put on a mustard-plaster, and prescribed a mixture. Meantime I looked at her; I looked at her, you know — there, by God! I had never seen such a face! — she was a beauty, in a word! I felt quite shaken with pity.”

Ivan Toergenjev (9 november 1818 – 3 september 1883)

Cover

De Nederlandstalige dichter, vertaler en sinoloog Lloyd Lewis Haft werd geboren in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, op 9 november 1946. Zie ook alle tags voor Lloyd Haft op dit blog.

Zigeunerspies (Leidse Hout)

Vergis je niet, mijn hart is geen berg,

geen machtige vermeerdering

van eens geworden afgescheidenheid:

Mijn hart is een levend weefsel

als een rauwe biefstuk zo groot,

Zo’n ding doet pijn als kolen,

en sintels, en losse rode bladeren

op alle paden branden die ik ken-

als ook de bomen, onverbloemd,

mij levend in hun leegte laten zien.

Hagel (Peking)

Het kan zo plotseling gebeuren:

zo’n hemelvol stenen

uit water geworden.

Komt het door meren in ’t zuiden,

woestijnen in ’t westen?

Zoek geen verklaring op aarde, want

dit is de werkelijkheid.

Ieder mens heeft dan ook

een masker voor. Kalm, geduldig,

verre boven de hoeken

der tienduizend straten, staat

één witte bus doodstil.

Lloyd Haft (Sheboygan, 9 november 1946)

De Duitse schrijfster Erika Mann werd geboren op 9 november 1905 in München als oudste dochter van de Duitse schrijver Thomas Mann. Zie ook alle tags voor Erika Mann op dit blog.

Uit: Wenn die Lichter ausgehen

«770 841 Industriearbeiter», bellte die Stimme aus dem Radio. Der Gast, dem man anstelle von Eiern den Völkischen Beobachter angeboten hatte, stand auf, streckte sich, gähnte und sah auf die Uhr.

«Eineinhalb Stunden», meinte er, «und noch kein einziges Wort über unsere Brüder im Sudetenland.» Was ist denn das, fragte sich der Fremde. Keiner hier scheint sich besonders zu begeistern. Eine sture Bande, diese Bayern, ein dickköpfiges, nachdenkliches Volk; sie lassen sich ihre Begeisterung nicht anmerken. In einer Ecke nahe beim Ofen saß ein kleines Mädchen und schrieb etwas auf. «Morgen hat sie eine Klassenarbeit», sagte der Wirt. «Also muß sie sich Notizen machen und sie auswendig lernen. Sonst bekommt sie eine Strafe.» «Wie viele Industriearbeiter waren das?» fragte das Kind. Niemand antwortete. Der Fremde hörte sich die Rede bis zum Schluß an. Auch als der wütende Führer geendet hatte und das Horst-Wessel-Lied verklungen war, blieb er sitzen. Er wollte sehen, welche Wirkung die Rede gehabt hatte, und er wollte mit dem Wirt reden, der wie ein freundlicher Mensch aussah. Der buschige Schnurrbart hätte einem Seehund zur Ehre gereicht, aber die klaren Augen in seinem kräftigroten Gesicht sprachen eine lebhafte Sprache. Doch er war kein gesprächiger Mensch. Auch an den Tischen wurde wenig geredet. Niemand erwähnte die Rede des Führers. «Hast du die Kirchenbanner gesehen?» fragte eine Frau ihren, ann. «Ich habe mindestens acht gezählt, allein fünf in der Bärenstraße.» Ihr Mann nickte. Ein verstohlenes Grinsen huschte über sein Gesicht. «So eine Unverfrorenheit!» sagte er. «Kirchenbanner hinzuhängen, wo es ausdrücklich verboten ist!» Zur Bekräftigung schlug er mit der Aachen Hand auf den Tisch. Dennoch hatte der Fremde den Eindruck, daß der Mann sich freute. «Eine ausgemachte Unverschämtheit», wiederholte er und warf dem Wirt einen fröhlichen Blick zu. Minuten vergingen, und die Gäste verließen nach und nach das Lokal. Der Fremde wartete gespannt auf alles, was er noch aufschnappen konnte, und blieb. «Wie viele Einwohner hat diese Stadt?» fragte er den Wirt und hoffte auf ein Gespräch. «120 nee», sagte der Wirt «Aber jede fünfte Familie hat kein eigenes Heim. Wir haben wenige Häuser und viele Mietskasernen. Macht ja nichts», fügte er rasch hinzu, als der Fremde die Stirn runzelte. «Es ist auch nur vorübergehend, bis wir die Wiederbewaffnung abgeschlossen haben. Natürlich hat die Waffenindustrie im Augenblick Vorrang. Erst kommt die Politik, dann das Privatleben.» «Jede fünfte Familie?» fragte der Fremde. «Woher wissen Sie das so genau?» Der Wirt lehnte sich mit seinem kräftigen Körper noch weiter über den Tresen. Nun, sein eigener, bereits verheirateter Sohn wohne noch hier im Haus; weil er keine eigene Wohnung bekommen könne.”

Erika Mann (9 november 1905 – 27 augustus 1969)

Cover

De Duitse schrijver Jan Decker werd geboren op 9 november 1977 in Kassel. Zie ook alle tags voor Jan Decker op dit blog.

Uit: Der lange Schlummer

“Als ich aus dem Rasthof heraustrat, fiel mir erst das höllische Getöse auf, das ich vor der Mahlzeit im Halbschlummer überhört haben musste. Sonderbare Vehikel, ganz ohne Pferde angetrieben, rasten mit Getöse und ungekannter Geschwindigkeit in einem fort auf einem breiten Verkehrsweg an mir vorbei. Sie schienen moderne Kutschen zu sein, doch ganz aus Metall. Ich hielt mir die Ohren zu, nur irgendwann brauchte ich meine Hände wieder, spätestens bei der Verrichtung der nächsten Notdurft. Hier in Thüringen, wo ich einst die schönste Naturstille genossen hatte, musste ich nun mit diesem infernalischen Krach haushalten. Dies gelang mir, indem ich störrischer Esel auf dem Seitenstreifen in Richtung Osten trottete, was mir der Stand der Sonne sagte, und dabei an die herrliche Bucht von Neapel dachte. Das war gar nicht klug, wie sich herausstellte. Ich zuckte nämlich bei jedem vorbeirasenden Geschoss zusammen, während diese hupten wie die Postkutschen, was den Beginn meines Spaziergangs zu einem ziemlichen Spießroutenlauf machte. Grob wusste ich, dass Gräfenroda zwischen Arnstadt und Gotha gelegen ist. An eine dieser beiden Städte wollte ich mich nun halten, um mein Quartier für die Nacht zu beziehen.

Du allein weißt, ob ich auf diesem Weg bis nach Sachsen gekommen wäre! Just da traf ich jedoch auf einen Russen, der mit einem riesenhaften Gefährt, das er Lastwagen nannte, auf dem Seitenstreifen haltgemacht hatte und eben ein rotes Dreieck aufstellte, das wohl Vorsicht gebieten sollte. Der gute Mann war völlig außer sich, an diesem unwirtlichen Ort einen Spaziergänger zu treffen. Er sagte immer wieder »Autobahn« zu mir, »hier Autobahn, nix laufen« – was in seinem krachenden Deutsch etwas kindisch klang, aber doch gut gemeint war. Mit den paar Brocken Russisch, die ich noch immer an mir trage, mahnte ich den guten Mann, er solle sich bloß um seine eigenen Sachen kümmern, mit mir sei alles in bester Ordnung.

Hier findest du einige Betrachtungen über die Verkehrswege der neuen Zeit, die mir sogleich in den Sinn kamen: Erstens scheinen mir diese mehr Rennstrecken als öffentliche Einrichtungen zu sein. So traf ich auf meinem ganzen Weg von Gräfenroda bis zur nächsten Ausfahrt keinen weiteren Spaziergänger an. Zweitens verleiten sie zu einer schrecklichen Hast, da ich die Fahrzeuge, wenn sie einmal an mir vorbeigestoben waren, nach einigen Sekunden bereits schon wieder aus den Augen verloren hatte. Höre, sie mussten noch am selben Tag zumindest bis Prag reisen können! Aber was hat man davon, wenn der ganze Weg übersprungen ist, der doch das eigentliche Lockmittel der Reise ist? Drittens gelangt man zu keinem Charakteristikum der Reisenden selbst, da sich diese in ihren Fahrzeugen zu verbergen scheinen. So reist man recht anonym in dieser modernen Welt herum, denke ich mir.”

Jan Decker (Kassel, 9 november 1977)

De Engelse dichter en schrijver Roger Joseph McGough werd geboren op 9 november 1937 in Litherland, Lancashire. Zie ook alle tags voor Roger McGough op dit blog.

The Sound Collector

A stranger called this morning

Dressed all in black and grey

Put every sound into a bag

And carried them away

The whistling of the kettle

The turning of the lock

The purring of the kitten

The ticking of the clock

The popping of the toaster

The crunching of the flakes

When you spread the marmalade

The scraping noise it makes

The hissing of the frying pan

The ticking of the grill

The bubbling of the bathtub

As it starts to fill

The drumming of the raindrops

On the windowpane

When you do the washing-up

The gurgle of the drain

The crying of the baby

The squeaking of the chair

The swishing of the curtain

The creaking of the stair

A stranger called this morning

He didn’t leave his name

Left us only silence

Life will never be the same

Kinetic Poem No.2

with love

give me your hand

some stranger

is fiction than truth

without love

I’m justa has

been away

too long in the tooth.

Roger McGough (Litherland, 9 november 1937)

De Engelse dichteres en schrijfster Anne Sexton werd geboren op 9 november 1928 in Newton, Massachusetts. Zie ook alle tags voor Anne Sexton op dit blog.

45 Mercy Street (Fragment)

Where did you go?

45 Mercy Street,

with great-grandmother

kneeling in her whale-bone corset

and praying gently but fiercely

to the wash basin,

at five A.M.

at noon

dozing in her wiggy rocker,

grandfather taking a nap in the pantry,

grandmother pushing the bell for the downstairs maid,

and Nana rocking Mother with an oversized flower

on her forehead to cover the curl

of when she was good and when she was…

And where she was begat

and in a generation

the third she will beget,

me,

with the stranger’s seed blooming

into the flower called Horrid.

I walk in a yellow dress

and a white pocketbook stuffed with cigarettes,

enough pills, my wallet, my keys,

and being twenty-eight, or is it forty-five?

I walk. I walk.

I hold matches at street signs

for it is dark,

as dark as the leathery dead

and I have lost my green Ford,

my house in the suburbs,

two little kids

sucked up like pollen by the bee in me

and a husband

who has wiped off his eyes

in order not to see my inside out

and I am walking and looking

and this is no dream

just my oily life

where the people are alibis

and the street is unfindable for an

entire lifetime.

Anne Sexton (9 november 1928 – 4 oktober 1974)

Cover

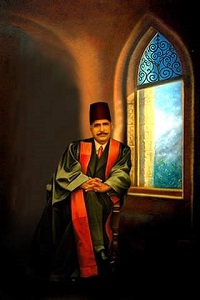

De Indische dichter en schrijver Mohammed Iqbal werd geboren op 9 november 1877 in Sialkot in het tegenwoordige Pakistan. Zie ook alle tags voor Mohammed Iqbal op dit blog.

The Withered Rose

O withered rose! How can I still call you a rose?

How can I call you the longing of nightingale’s heart?

Once the zephyr’s movement was your rocking cradle

In the garden’s expanse joyous rose was your name

The morning breeze acknowledged your benevolence

The garden was like perfumer’s tray by your presence

My weeping eye sheds dew on you

My desolate heart is concealed in your sorrow

You are a tiny picture of my destruction

You are the interpretation of my life’s dream

Like a flute to my reed-brake I narrate my story

Listen O rose! I complain about separations!

Sympathy

Perched on the branch of a tree

Was a nightingale sad and lonely

‘The night has drawn near’, He was thinking

‘I passed the day in flying around and feeding

How can I reach up to the nest

Darkness has enveloped everything’?

Hearing the nightingale wailing thus

A glow-worm lurking nearby spoke thus

‘With my heart and soul ready to help I am

Though only an insignificant insect I am

Never mind if the night is dark

I shall shed light if the way is dark

God has bestowed a torch on me

He has given a shining lamp to me

The good in the world only those are

Ready to be useful to others who are

Mohammed Iqbal (9 november 1877 – 21 april 1938)

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

De Amerikaanse dichter en bibliothecaris Michael Derrick Hudson werd geboren in 1963 in Wabash, Indiana. Zie ook alle tags voor Michael Derrick Hudson op dit blog.

Baby Zach and the Winter Squash

It’s his favorite food, she told me, but I have no idea

what it is. Me neither, but it sounds very nutritious

and wholesome in an apocryphal

First Thanksgiving way: The Legend of Squanto’s

Delicious Squash and how he had to beg a starving

bluejawed Pilgrim to try it, scowling

while he masticated with theological rectitude and

pigheaded paranoia despite the evidence

of toothless old women and dozens of drooling,

happy babies gumming down the stuff with gusto

in the prosperous Wampanoag village

slightly hazy from the cooking fires where baskets

bulged with corn and blueberries and raccoon pelts

hung everywhere until finally

the trespassing homespun homicidal grouch

proclaimed: Indeed, ’tis a wholesome victual and

added it to the available proof of God’s preferment.

Michael Derrick Hudson (Wabash, 1963)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 9e november ook mijn blog van 9 november 2017 en ook mijn blog van 9 november 2014 deel 1 en eveneens deel 2.